During the American Seed Trade Association’s Virtual Policy and Leadership Development Conference, experts looked at the economic outlook of different crops for 2020.

If there’s one thing we can all agree on in 2020, it’s that COVID-19 has not just thrown us off of our game but has created a new one for us. While our personal routines have shifted in various ways, the coronavirus has drastically changed the way we do business. And the agriculture and seed industries are no exception.

Seed associations like the American Seed Trade Association (ASTA) are taking this new challenge in stride, moving ahead and adapting to the change as they come.

“We know this has been a very challenging year,” John Latham, upcoming chair of ASTA, said during the Virtual Policy and Leadership Development Conference (PLDC Virtual). “We want to remind you that ASTA is here and is working hard for you to continue our work of promoting the seed industry … We can’t wait to get back together with you in person.”

ASTA brought in experts from across the industry for the PLDC Virtual event, to give their members an economic update on both field crops and produce, and how COVID-19 has affected and shifted business during this unprecedented time.

Consumer Behavior Becomes Chaotic

ASTA hosted the Economic Outlook on the Seed Industry: Produce Session, in which two experts shared their thoughts on the produce side of the seed industry, and how COVID-19 specifically has affected them. Steve Lutz, senior vice president of insights and innovation of Category Partners, and Adam Brohimer, vice president of Category Partners, both noted the vast changes the produce industry faced in the last few months.

“The pandemic is unlike anything we’ve seen in our lifetime,” Lutz said. “I have been pulling data for over 20 years and looking at retail performances across the supermarket. Obviously, nothing like this has been experienced by any of us: the flocking to the stores and the wave of pantry loading.

“The real question is: What’s the impact?” Lutz said. “How are consumers changing? What can we anticipate in the coming months as we actually move through this quarantine pandemic? Once we emerge, hopefully consumers have the opportunity to move back to more normal types of purchasing behavior.”

Lutz states there were visible shifts in shopping patterns from consumers each week, which came across in four “waves”:

- Wave 1: January to March 7 — Awareness

- Wave 2: March 8-21 — Pantry Loading

- Wave 3: March 22 to April 18 — Quarantine Easter Flip

- Wave 4: Post Easter — New Baseline

“In Wave 1, we really began to see that obviously consumers were aware of COVID-19 in January,” Lutz said. “It was fairly and widely talked about in the media, but we didn’t really see the change in behavior until the first week of March.”

Lutz noted that after the awareness phase came, the pantry loading phase followed, which quickly moved into what he notes as the “Easter Flip,” time period.

“We simply call it Easter Flip because when you look into the year ago data, you always have to account for Easter week sales,” he said. “It’s a fairly large week for supermarkets, so whenever you are looking at year ago data, you have to account for when Easter hits in first quarter.”

Finally, what they believe is the new baseline describes the time period from the first of May to the date of the presentation, June 2, 2020.

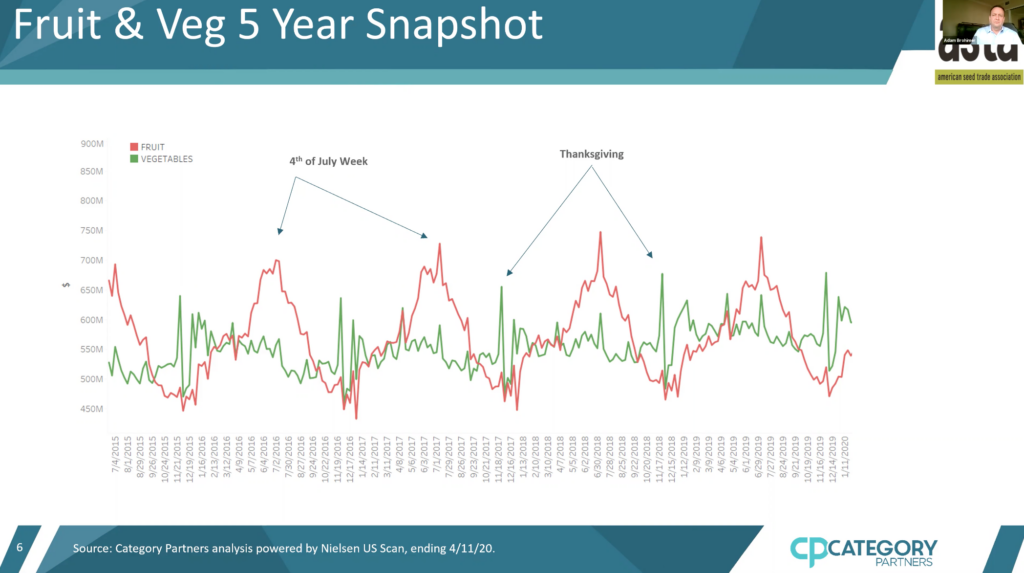

From the graph above, it’s easy to see both the largest points of data from fruits and vegetable sales: for fruits, it’s Fourth of July, while for vegetables, it’s Thanksgiving. However, as the pandemic hit, there was a noticeable shift.

“There was an unprecedented shift in sales — there’s no time in the last five years, maybe even 20 years, where vegetable sales in retail exceed fruit,” Lutz said. “There may be individual weeks where it is higher than fruit, but as a total, the highest week for vegetables is never higher than the highest week of fruit.”

Lutz noted that when the pandemic hit, vegetables screamed by fruit and set a sales record. Because of this, Lutz says that they saw that consumers didn’t know how to respond to the pandemic.

“Maybe people were going out and buying toilet paper,” he said. “But other than that, it was really: ‘Well, what do I do? How do I respond?’”

“Looking at the retail sales, it was near impossible to tell what was flying off the shelves,” Brohimer said.

Brohimer noted that even when certain areas of the United States began to open — in this case, they looked at Georgia’s reopening process — there wasn’t a dramatic spike to go out and spend money.

“Consumers, even when they had the option to act in a more normal manner, still were hunkered down,” he says. “As economies in various states begin to reopen more and more, there’s still going to be this kind of pullback and consumers will be taking a ‘wait-and-see’ attitude.”

But it’s been a real vegetable phenomenon, as Lutz said.

“Vegetables were up 28.5%,” Lutz said. “Look at the ingredient items: bell peppers, mushrooms, potatoes, broccoli, onions … all with 30% increases in dollars and volume over the previous days. In the pantry loading period, potatoes, for the first time I’ve seen in recent history, outsold packaged salads.”

But the question both come back to: what are the real impacts of COVID-19 on retail?

“What we think is that consumers will continue to act and shop and prioritize differently in the same ways they did during the Great Recession,” Lutz said. “Consumers change how they shop, they change where they shop, and they redefined discretionary key food attitudes.

“They’ll look for the safest, healthiest foods possible,” he continued. “They’ll look for staple foods, comfort foods and they’ll stretch trip frequency out to try and stretch their dollar. Above all, quality always comes into play because if you have fewer dollars, you can’t afford to take chances.”

COVID-19 Disrupts the Supply Chain

During the Economic Outlook of the Seed Industry: Field Crops session, two experts joined the discussion to present some of the challenges facing both farmers and the industry during COVID-19: John Newton, chief economist of American Farm Bureau Federation and Seth Meyer, research professor and associate director of the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri.

At the beginning of the year, Newton said there was some optimism — with the phase one deal with China signed in mid-January, with USMCA moving forward this year and with the U.S.-Japan trade agreement, it seemed like we were rounding third base and coming home with restoring loss of demand in our export markets. Meyer agreed with Newton and said that we were in a record year for corn harvested, which gave us a general rebound in production in comparison to 2019’s prevent plant acres.

“There was a big rebound in acreage for both corn and beans,” Meyer said. “We probably recovered most of that additional prevent plant last year.”

“At the outset, we thought 2020 was going to be a race between supply and demand,” Newton said. “And if demand accelerates as we hoped it would, we thought we’d finally see commodity prices turn a corner.”

Newton said that they were hopeful demand and export markets would lead to higher prices.

“We needed it,” he said. “We’re in the eighth year in a down farm economy. We’ve seen a 30% decline in net cash income, and that rivals what we saw after World War II when we had a 30% decline. Many people like to compare where we are today with the 1980s, where we saw a 45% decline in net cash income over an eight-year period.”

Then, in March, COVID-19 threw a wrench into some of the hopes of a better economic outlook.

“One of the first impacts we saw from COVID-19 was on restaurant demand,” Newton said.

When you look at how Americans accessed food in 2018, Americans spent $1.7 trillion on food. More than half of that — a whopping $678 billion — was spent at restaurants, with another $253 billion being spent on other food away from home.

Of course, this immediately caused some problems in the agriculture industry. The dairy industry faced market loss and had to dump milk. Idaho reported that there were potato growers who faced food distribution companies canceling their orders for frozen french fries.

“While we tried to move some of that through the retail channel, we started observing challenges of a disruptive supply chain,” he said.

“In March, we did see the panic buying push retail sales and grocery stores up to a record $73 billion,” Newton said. “In April, we continued to see strong grocery sales at $63 billion, but what we lost was a very significant decline in food service and drinking expenditures, which was down from February 2020 about 47% in April.”

In terms of the ethanol industry, there were two events that really hit that market: the oil war between Saudi Arabia and the United States that produced an increase in production which resulted in a sharp decline of oil prices, and the stay-at-home orders and their impact on gasoline demand.

“For 2020, if folks drive a mile less or 10% less, that means you’ll have 10% less ethanol demand over the course of the year,” Meyer said. “When we switch to 2021, the Department of Energy is saying we’re going to need 5% less motor gasoline. Really what we see in 2021 demand in ethanol domestically is dependent upon what the EPA says.”

Meyer said this dependent on whether or not they want to put pressure on that system to absorb more, or if they want to account for lower demand by setting a lower RFS.

“We’ve seen ethanol prices drop sharply into negative profitability territory,” Newton explained. “We’re seeing ethanol plants start to idle capacity across the country or close down. As a result, ethanol production has declined about 40% in the month of April. We’re several weeks or months away from seeing ethanol demand back to where it was.

“The damage to agriculture is significant,” Newton said. “That’s why additional support is so desperately going to be needed in the next couple of months.”

“Uncertainty is likely to continue on these things,” Meyer says. “The length and breadth of COVID impacts will tip the scales on many things here. We don’t really know the extended supply chain impacts for 2021.”