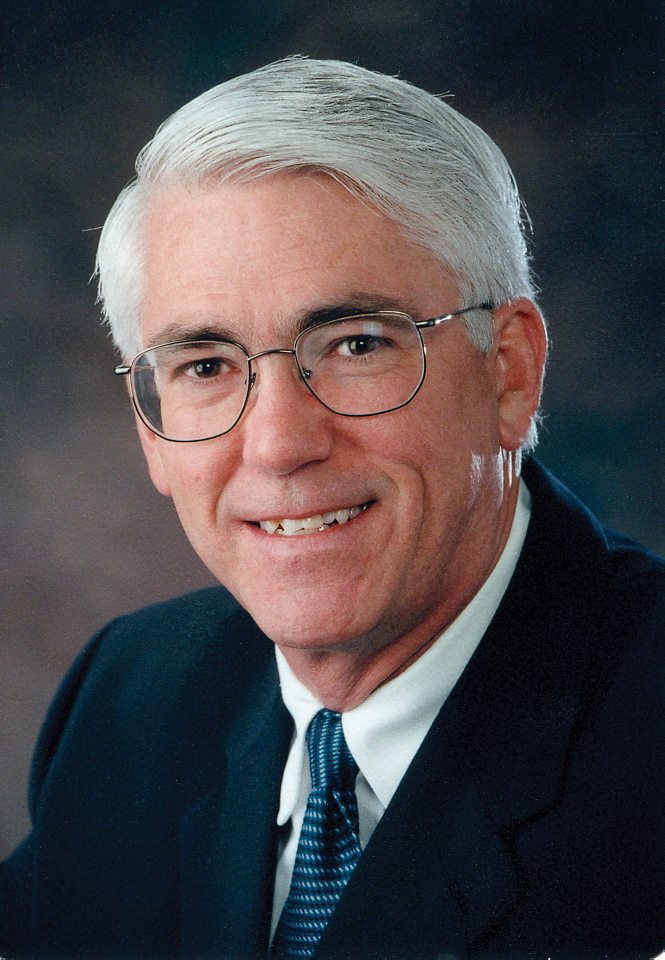

is dedicated to delivering solutions and empowering people and organizations to solve complex problems related to international agricultural development and global food security. His career experience and international credentials include Extension education, agronomy and administration.

Seed systems throughout much of sub-Sahara Africa are quite informal and lack the structure we’ve come to know in North America. Those systems are challenged to function under, or in spite of, innumerable constraints. Yet, many are functional.

Recently, I got a firsthand look at a number of seed systems in Mali, Niger, Uganda, Kenya and Malawi. But to understand the seed systems, you must first understand the farmers.

Most farmers are smallholders, operating on one to seven acres. Their principal crops are open- or self-pollinated (pearl millet, finger millet, sorghum, groundnut, common bean) and not widely adapted across the regions. Families consume much of their crop production, and excess grain cannot be readily marketed. Grain is too precious to feed to animals. Additionally, mechanization is nonexistent or generally not affordable, and cash is spent on food or school tuition.

Now, let’s hone in on the themes within the seed systems. The private sector seed industry is mostly absent from the semi-arid tropical regions of sub-Sahara Africa. The economic picture is insufficient to drive a commercial seed industry that can develop, distribute and support improved seed products.

Common practice dictates that seed be saved and replanted season after season. As you move closer to the equator, farmers enjoy two growing seasons per year. Some seed might be shared but seldom is it sold as is the case in western Africa.

Improvements are made to local varieties and newer varieties are developed by international public sector breeding programs, such as CGIAR, the International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture. Beyond the initial challenge of developing an improved variety, the various CGIAR international plant breeding programs face other hurdles.

In lesser-developed regions, without a commercial seed sector, how are farmers to become aware of the availability or potential of a given improved variety? Typically, partner networks must be painstakingly crafted within each country. Often these networks begin with the national minister of agriculture and include any existing national plant breeding or seed certification authorities. Fledgling seed companies might even be engaged. Even when these networks are established, will farmers have the financial ability to acquire improved seed? Out of such realities are born informal seed systems that disseminate improved seed.

For example, in Niger and Mali, 20 to 35 candidate selections of improved open-pollinated varieties of sorghum and pearl millet are distributed each season to villages for entry into on-farm trials. Trials are coordinated through village leaders who then select 25 to 30 farmers to plant the trials. Each candidate selection is evaluated in the field for agronomic performance, and the grain is evaluated within the community for culinary preference. Farmers are encouraged to save and plant seed from all the improved candidate selections. This is done irrespective of whether or not the selection advances to the national level for official varietal registration. If farmers like the candidate seed, they will save and replant this “improved” seed.

Another example is in Uganda where the national plant breeder coordinates with emerging seed companies, or farmer associations, that are interested in receiving and multiplying officially recognized improved seed varieties. The seed company initially receives small quantities of foundation class seed and contracts individual members to produce certified seed. The certified seed is then sold by the farmer associations to members, other farmers, government subsidy programs and non-government organizations that supply planting seed to farmers.

In Malawi, discussions revealed success with the seed bank concept. Within six months, 95 percent of farmer loans in one village had been repaid. The “seed” in “seed bank” relates to seed money for inputs such as fertilizer, insecticide and seed. At the village level a micro-loan is obtained. Village leaders determine which farmers are serious about improving their ag enterprises, and worthy farmers receive small loans.

Loans can be paid back in-kind. The repayment factor is multiplied by two. So, if one borrows 2 kilograms of groundnut seed from the seed bank, he can repay the loan by returning 4 kilograms of groundnut seed. If you borrow to buy three chickens, you owe six chickens. It’s simple and appropriate!