Nectar doesn’t always taste so sweet, but honeybees and other pollinators still feed on it. Now UC Davis community ecologist Rachel Vannette has discovered why pollinators continue to forage on “toxic” or bitter-tasting nectar, despite what should be a deterrent.

In newly published research in the journal Ecology, Vannette notes that floral nectar is produced by many plants to reward pollinators, but this sugary secretion often contains chemical compounds that are bitter tasting or toxic, which should deter pollinators. Plants including citrus, tobacco (Nicotiana), milkweed (Asclepias), turtlehead (Chelone), Catalpa, and others produce nectar containing bioactive or toxic compounds.

“This poses a paradox of toxic nectar: why are deterrent or harmful compounds present in a resource intended to attract pollinators?” she said. “One hypothesis is that these compounds reduce microbial growth, which could otherwise spoil the nectar resource.”

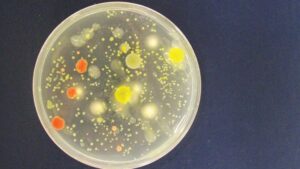

Vannette, an assistant professor in the UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology, and Tadashi Fukami, associate professor at Stanford University, tested this hypothesis by growing yeasts and bacteria in sugar solutions spiked with chemical compounds found in nectar.

Contrary to expectations, the chemical compounds only weakly inhibited microbial growth in most cases. Some microorganisms even grew better in the presence of plant compounds such as nicotine. But most surprising, they found that microbial growth reduced the concentration of the toxic chemical compounds in nectar solutions.

These microbial effects on nectar, in turn, actually increased consumption of nectar by honeybees, she said.

“We found that microorganisms in nectar can both reduce the concentration of some plant compounds in nectar and increase consumption of nectar that does contain these compounds. This indicates that although ‘toxic nectar’ does not strongly inhibit microbial growth, microbes modify the palatability of nectar to pollinators, which can change foraging behaviors and may reduce selection on this trait,” Vannette said.

Nectar microbes bring more pollinators

Another hypothesis for why some plants have bad-tasting compounds in nectar is that it might keep the nectar exclusive to a few pollinators, keeping down micro-organisms and deterring other non-pollinators looking for a sweet treat. The new work, however, shows the opposite: microbes aren’t much affected by the secondary compounds, and microbe growth actually seems to encourage more pollinators to visit flowers.

The research, “Nectar Microbes Can Reduce Secondary Metabolites in Nectar and Alter Effects on Nectar Consumption by Pollinators,” appears in the journal Ecology.

The research was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and Stanford University.

Future work will examine how microbial modification of nectar traits influences floral attractiveness, how microbial growth may modify the specificity of plant-pollinator interactions, and if microbial effects vary among plant species.

Vannette joined UC Davis in September 2015. “I am interested in understanding and predicting how microbial communities influence interactions between plants and insects,” she said. “In the Vannette lab, we use tools and concepts from microbial ecology, chemical ecology, and community ecology to better understand the ecology and evolution of interactions among plants, microbes and insects.”

—Kathy Keatley Garvey writes about all things insect-related for the UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology and UC Division of Ag and Natural Resources. For more insect news, follow her Bug Squad blog.