This is the message of Craig Cormick, a leading science communicator who will be addressing community attitudes to new food technologies at Australia’s 2016 ATSE National Technology Challenges Dialogue: Agribusiness 2030 being held on 15 and 16 June in Sydney. It will bring together Australia’s top agriculture and agribusiness leaders and innovators from research, industry and government.

“Arguing about the validity of the science behind new food technologies is about as effective in changing attitudes as taunting and name calling,” said Cormick, who has faced plenty of taunting and name calling as his academic and professional careers have centred on public acceptance of contentious science and technologies such as biotechnology and nanotechnology.

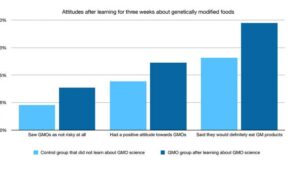

“Attitudes that were not formed by logic and facts are not influenced by logic and facts.” He explained that when presented with information that is complex, people tend to make emotionally-based judgements, driven by values or worldviews, and any information that doesn’t align with their values or worldviews tends to be rejected or dismissed.

“Scientific evidence has very little impact on anyone who already holds a strong belief that a technology, such as biotechnology, is not safe,” he said.

“Social research shows that tendencies towards conspiracy theories are strong predictors for anti- GM positions.

“Studies have shown that worldviews and beliefs, rather than age, gender, or other standard demographics, are better predictors of people’s attitudes to GM foods, climate change, vaccination, fluoridation or to science and technology (S&T) in general.

“We can see this played out in the seemingly contradictory positions of some members of the community. For instance, people with strong values on the sanctity of nature demand we respect the science on climate change, but then advocate we reject the science on genetically modified crops. Meanwhile people with strongly pro-development values tend to demand we respect the science on GM crops, but advocate that we reject the science on climate change.

“People, however, are receptive to messages that align with their values. If you can identify people’s values and then frame a message to align with those values, you have a much higher chance of not having your message rejected out of hand,” he said.

Craig explained that there are four key segments of the population by values to S&T: About 20 per cent of the population – the concerned and disengaged – are the least enthusiastic about the benefits of S&T. The second group (23 per cent) are risk averse, tending to be less positive towards the benefits of S&T generally, and biotechnology specifically. The third group (28 per cent) are ‘the cautiously keen’ and have relatively high interest in S&T but can be very risk averse so have the highest agreement that ‘children should be protected from all risks.’ The final group (about 25 per cent) are the science fans – who are the most positive towards S&T and express greater agreement that ‘new technologies excite me more than they concern me’.

“Getting new technology accepted is rarely about the quality of the science. For many people it is more about meeting their concerns that children will be safe, or about feeling less confronted by the pace of technological change.

“Our messages about new technologies need to address these concerns more than explaining the science,” he added.