Sustainable Agriculture in the EU – Part 1

Almost 50% of the EU territory is covered by farmland (both arable land and permanent grassland) leaving a key role for agriculture to play in land management and bestowing it a big responsibility in the preservation of natural resources. The EU Commission calls the desired relationship between agriculture and the environment “sustainable agriculture” and calls for management of natural resources in a way which ensures that their benefits are also available for the future. European Seed took a deep dive into Sustainable Agriculture and sat down with Marc Cornelissen, Sustainability Lead for Seeds and Traits at BASF, and President of the European Technology Platform (ETP) “Plants for the Future” to get his take on the topic.

This is the first article in the two-part series in Sustainable Agriculture in Europe. Part 2 will appear in the following issue of European Seed.

European Seed (ES): Marc, in a nutshell, what is sustainable agriculture?

Marc Cornelissen (MC): I guess you are raising immediately the key question. The term “sustainable agriculture” has been defined by multiple parties across the globe and consequently is differently understood in the details. The different definitions do share however the vision that agriculture should have a long term environmental and economic viability and deliver to today’s society and its future generations the necessary output in diversity, quantity and quality.

Such vision does breathe the importance of meeting societal demand, economic requirements, and environmental targets with a long-term perspective, and immediately highlights the issue that depending on where you are on our planet, the “as is” situation will be quite unique and will show different shortcomings.

Ideally, the sector, policy makers and society advance their common understanding on what the desired embodiment of “sustainable agriculture” is, and, equally important, how it relates to influential themes like climate change mitigation, energy transition, healthy diet, business continuity, digitalization and big data, robotization, and social services. It is in this complex, multi-dimensional space that the migration of agriculture to sustainable practices and products will take place and needs to be promoted through smart supportive policies.

ES: Where did we go wrong in the past?

MC: The historic innovations in agriculture focused primarily on raising productivity and quality, and not on avoiding negative impacts on the environment. Agriculture has now arrived at a stage where data show that the level of exploitation of the earth’s resources for food, feed fuel and fiber production has damaged the diversity and quality of flora and fauna, and is about to cause irreversible changes to the earth’s climate. Just for the record: agriculture uses 37% of the world’s land, 70% of all fresh water, and 30% of global energy consumption (agro-food sector).

When transitioning to sustainable agriculture, the prime challenge is to find ways to break out of the rigidity of the socio-economic system in which agriculture is fully locked in. The choice of crops, transport, storage, processors, producers, retailers, consumer behavior, pricing and so on, are all in balance. These elements constitute a predictable flow of materials and financials, and translate into concrete jobs, infrastructures, equipment etc. Changing such an equilibrium requires a cautious and holistic approach in which switching costs and other risks are properly addressed.

The agricultural value chain is offering here some unique opportunities: being probably the oldest value chain in the world, it offers employment to nearly 30% of global society , and is characterized by a broad diversity of products, production methods, input needs, waste streams, supply chains and business models. This implies that to increase sustainability of agriculture while further growing and tailoring its output, there is an unprecedented variety of short-, mid- and long-term wins possible. The nature of these would depend on the geographic location, local culture and policies, product type(s), ways of producing, and prevalent business models. In addition, critical backwind is offered through policies that encourage customers to shift to sustainable, healthy food and recyclable products. Altogether, the unique socio-economic setting of agriculture offers fundamental levers to rethink how agriculture should produce its future products in different regions and be “sustainable”.

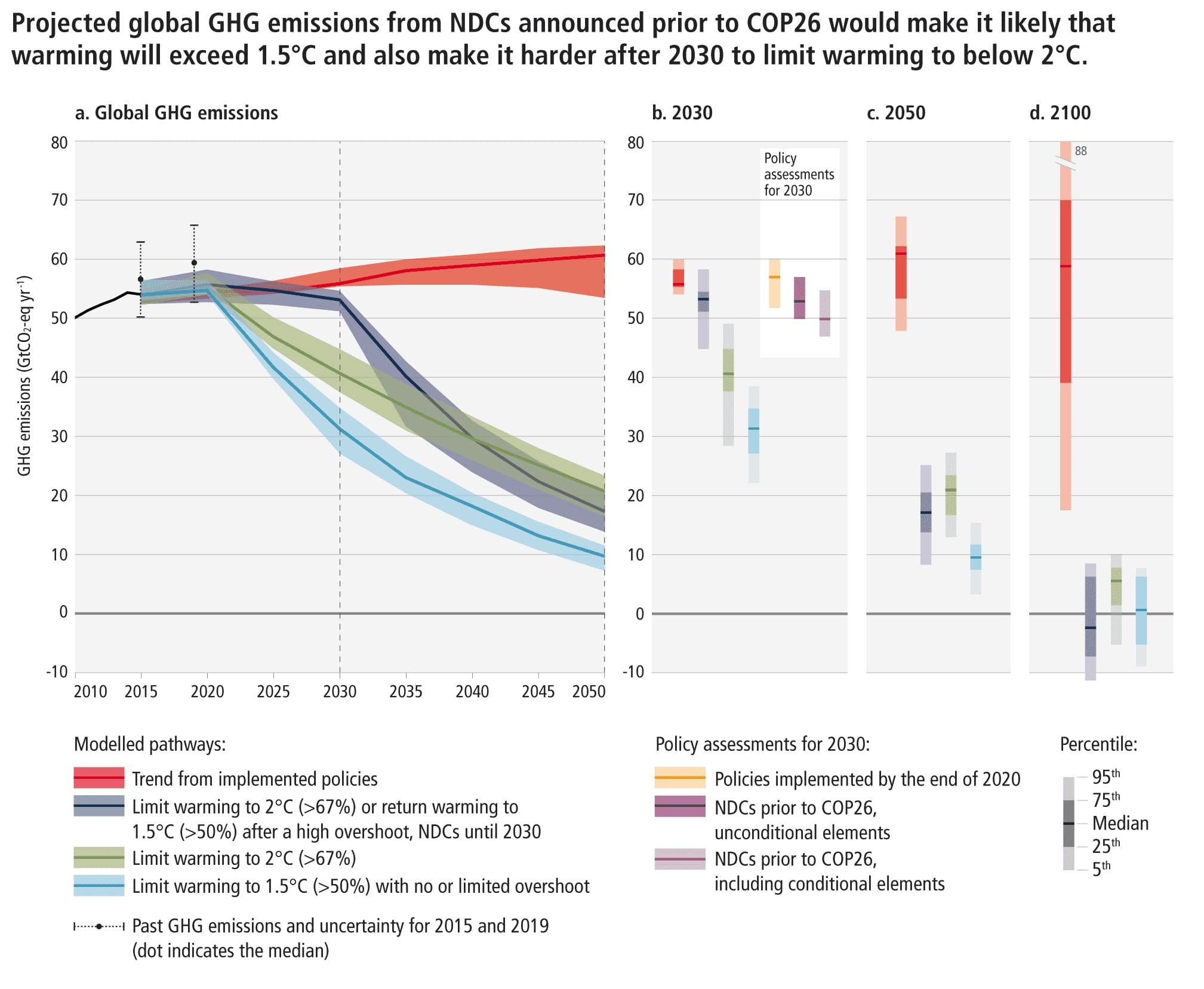

ES: There were and are numerous indications about climate change. Are we acting sufficiently fast?

MC: As a member of society, I am of the opinion that we are not well informed about the impact our personal activities and choices have on climate change. A great example comes from a 2017 Canadian study (ref 1.1)that compared a ranking of the most impactful measures a person can take to minimize environmental impact, versus the information provided in educational work. The observation was that three of the top six high impact measures (one child less, car-free life, one air travel less, green energy, green car, plant-based diet) were not even mentioned once across the 10 study books scanned.

Similar information gaps on high impact actions were found when scanning government documents coming from Australia, the EU, the USA and Canada, that aimed at advising on how a person can reduce GHG emission. Without the proper information and guidance, it is unlikely for society to adopt a different lifestyle behavior. The same somehow applies to the agricultural sector: it is clear that fossil-fuel related activities or products need to be replaced by alternatives, and that the ongoing energy transition will be the driver. It is therefore not very meaningful only to look at the aggregated figures of environmental impact of the agricultural sector. The bona fide innovation space for agriculture lies in (1) minimizing or even countering non-fossil fuel related GHG emissions, and (2) mitigating negative impacts on climate by developing cropping systems with improved resilience to dynamically changing biotic and abiotic stresses.

The former can be addressed by both technological and business innovation and deals with land use and land use change. In the end, non-fossil based GHG emissions need to be considered as an amount of GHG per unit product, rather than per unit land. This implies that with the same land use, emissions may lower through (1) gains in productivity using the same impact practices, (2) maintaining productivity using lower impact practices; or (3) elevating the use fraction of the biomass produced through co-product strategies.

Farmers do engage already today in cases where reduction of GHG emissions coincide with improved farm economics. This relates to choices of seeds, traits, chemistry, other inputs and cultivation practices. A second route to reduce non-fossil fuel related emissions may be driven by a shift in policies and consumer demand and would open up options to smartly repurpose land use. Examples are the departure from cultivating crops for fuel (USA 40% of all corn, EU near 100% of all rapeseed as part of an economically essential co-product strategy), and a several percentage points diet shift to plant-based protein, thereby stabilizing or reducing acreage requirements for feed production and paving the way for alternative cropping systems with more agro-ecological approaches.

The latter innovation space, mitigating negative impacts of climate change, has both fast track and traditional R&D options. Because of the unique cultivation conditions each farmer is facing, and the volatility of these conditions, the fast track and traditional R&D innovations are desirably complemented with solutions that provide farmers with information tailored to their situation. It basically is about introducing big-data approaches into farming. This is a new playground where parties enter a learning track, and where data governance and stewardship as well as business models need to be worked out to arrive at a win-win situation for all stakeholders involved.

To get back to your question “are we acting sufficiently fast”: the energy transition has kicked off and is gaining momentum, thanks to a complex mix of growing demand, innovation efforts, structural enablement and improving economics. The bona fide innovation space to accelerate sustainable agriculture is as discussed above in my opinion still in its lagging phase. A primary hurdle is that sustainability features are not yet offering convincing business value propositions. This requires a sector-wide agreement on priority agricultural sustainability indicators and how to weigh these, as well as an economic appreciation of best-in-class products with such features throughout the value chain. In some aspects it is about creating market space for “environmental damage control”. I guess the ball will start rolling as soon as conditions have been developed in which sustainability specifications can create the necessary market-pull and become an integral part of branding and procurement strategies across the value chain. The good news is that both the sector and EU policy makers are actively looking into this.

ES: Is there a solid baseline from where we can judge?

MC: The short answer here is “no”. Sustainability is about understanding the long-term impact of human actions and current agricultural life cycle analysis (LCA) models are not capable of predicting long-term consequences. Consequently, the sector is forced to enter a multi-year learning period. It is critical to start measuring relevant parameters in a harmonized and standardized way, and to develop meaningful modelling assumptions that over time get reworked and validated as real-life data develop. It should be acknowledged that farmers may be stimulated to start measuring and reporting on practices using criteria that after several years might turn out not to be informative about long-term sustainability.

It is therefore crucial to put in place instruments to engage stakeholders and to reward participation rather than outcome. It is initially all about early demoing and learning. This learning goes beyond rating sustainability as it is also about how to guarantee good data stewardship and to deal with extra costs, complexity and possibly operational time delays. A sector-wide alignment on how to proceed here is essential and should be managed with the necessary agility while insights sharpen. The challenge is to bridge time while parties learn, and possibly discover that their processes and products don’t meet the companies target market profile.

To get industry-wide embracement and to allow parties to adjust their business portfolio without putting business continuity at risk, the installment of an appropriate grace period is a key instrument. It may be worthwhile to take lessons from the EU transport sector that, back in 2012, was given binding targets to lower CO2 emissions of their fleet-wide sales in a phased and progressive manner, to arrive ultimately at zero-emission vehicles.

A meaningful baseline starting point for the agricultural sector is offered by a 2018 study (ref. 1.2) that brings together peer-reviewed farm and production data from across the globe into a harmonized and standardized format. The dataset comes from 44.000 farms and delivers some totally new insights. It appears that for a broad range of agricultural products the environmental impact per kg of product may differ by as much as a factor 5 and depends on where and how the product is produced. The implication of this study is that solutions to reduce environmental impact are achieved by focusing on specific products, production places and practices, rather than by installing national or regional measures. This initially purely scientific research is now receiving funds from WWF to set up “Hestia”, an open access data repository, that will harbor curated and harmonized environmental data from farms and production.

The aspiration is to offer a gold-standard reference data source for environmental scientists, value chain players and policy makers. The platform will go live mid-2021 and aims at growing its scope and informative value across product classes over time. This work is complemented by the European Commission amongst others that is developing methodology to use data such as are gathered in Hestia, to calculate the environmental footprint of agricultural products and processes from cradle to grave.

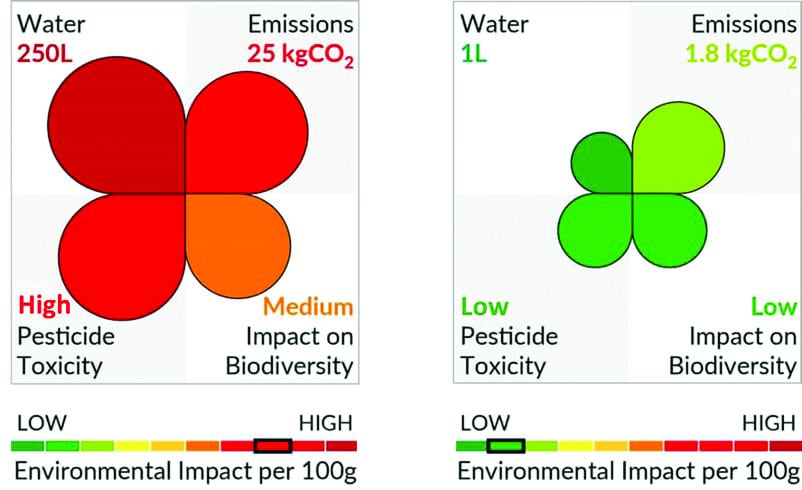

Developing and working with a baseline is a “must-do”, and as climate change is becoming visible to all, the challenges emerging in agriculture may start to resonate with society to a level that the desired momentum from a market pull perspective is going to be met. A baseline and the installment of a sustainability label may offer consumers the opportunity to make informed decisions on what they want to promote. The reach of this is enormous as traceability and labelling would allow European consumers to influence production and transport practices in and outside of Europe. Moreover, it could further propel the digitalisation within the agricultural value chain.

Figure 2 Labelling concept for food using a color scheme familiar to the consumer. In the example four candidate priority sustainability indicators are integrated with production and yield an aggregated environmental impact per 100 grams of product. Indicators may be replaced over time when priorities shift.

Reference for figure 2: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/oct/10/we-label-fridges-to-show-their-environmental-impact-why-not-food

Ref 1.1 Set Wines and Kimberly Nicholas, Environmental Research Letters 12, (2017), https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541

Ref 1.2. Poore, J. and Nemecek, T., Science 360, 987-992, (2018), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325532198_Reducing_food%27s_environmental_impacts_through_producers_and_consumers