Ellen Sparry has had a busy year, to say the least.

On Feb. 1, 2021, Canada’s new national seed organization — Seeds Canada — went live. Made up of four amalgamating partners — the Canadian Seed Trade Association, Commercial Seed Analysts Association of Canada, Canadian Seed Institute and Canadian Plant Technology Agency — Sparry agreed to serve as president to lead the board into uncharted waters.

Uniting a large chunk of Canada’s seed industry under one banner had been talked about for many years, but never saw the light of day until now.

“Discussions have gone on for over a decade. I think it was 2009 when it first came up, so it has been a goal for quite a while. For a long time, we were a somewhat fractured industry,” says Sparry, who serves as general manager for Ontario’s C&M Seeds.

The amalgamation of the four partners comes at an important time in the country’s history, as efforts are underway to modernize both Canada’s seed regulatory system and novel food regulations. The desire to lobby for itself as a united industry — to speak with a single voice — was a major driving factor in the formation of Seeds Canada.

“We knew from meeting with government over the years that we needed to get ourselves better aligned. We now have over 200 members from all areas of the industry under one roof — seed analysts, plant breeders, distributors, producers and many others,” Sparry says.

If anything defined 2021, it was just that — a need for alignment. Whether it was a world struggling to harmonize a patchwork of travel protocols that saw some countries shun certain vaccines, or a budding energy crisis that saw fuel costs begin to skyrocket, the year was a roller coaster that left many trying to steer their business through turbulent waters while doing the basic business of seed.

“The major challenges, regardless of the pandemic, are high quality seed production, intellectual property protection and [increasing] innovation,” says May Kanokwan Chodchoey, executive director of the Asia-Pacific Seed Association (APSA).

Ultimately, seed companies across the Asia-Pacific region need the tools and framework to provide high-quality seed to farmers. This means greater genetic improvement, achieved through research and development. APSA looks to enable the seed industry to make improvements for farmer customers — something even more challenging than usual in a pandemic.

In the early stages of the pandemic, APSA deployed three detailed surveys to its members to determine the impact it was having on the seed industry.

Seeds Canada President

“We saw at the time the pandemic hit last year that many countries asked for government support in terms of seed movement because this was the first factor that we saw had a huge impact,” she says. “As we studied more, we learned that transportation was really difficult for companies to find.”

Freight costs increased drastically in the region, if transportation was available at all. However, APSA recently re-deployed the survey to find many of the challenges first experienced in the pandemic have been addressed.

“We still see room for improvement in international seed movement,” she says. In addition, company representatives told APSA they’re taking advantage of technology more in fields and in situations where it’s not safe for them to appear in person

As a way to promote and facilitate seed business and smooth trade within the Americas and globally, it’s vital to work on the harmonization and simplification of regulations. A common approach to these matters is essential, according to Diego Risso, executive director of the Seed Association of the Americas (SAA).

“Seed movement is one of the challenges that most seed companies struggle with,” Risso says.

“There are also a lot of challenges in the Americas with the implementation of UPOV 91, since there are many countries under UPOV 78 Act, while few others have already moved to UPOV 91. There has been some progress on this matter, but it’s extremely slow considering the benefits that could bring to farmers, breeders, governments and other stakeholders.”

SAA has four primary working groups on four critical topics: intellectual property, phytosanitary, seed treatments, and biotechnology & plant breeding innovation. These groups are being led by senior experts bringing knowledge, expertise and management to assure successful results.

“We’re really working to keep our members engaged within these groups,” Risso says. “That way, they can feel part of the association and see its benefits.”

Engaging an Industry

Engagement is a challenge Sparry is intimately familiar with, and the Seeds Canada amalgamation brought that challenge to the forefront and kept her up at night.

Canada exports over $700 million annually in seed to over 100 countries. Sparry herself as been very active at the international level, having been an active member of the International Seed Federation.

“Our participation in the global market is extremely important. Canada plays a big role on the global stage and with everyone now at the table we are in a better position to grow that market even more.”

The amalgamation was not without its bumps, though. Canadian Seed Growers’ Association members ultimately voted no to the amalgamation, meaning a second vote had to be held among the four remaining partners before Seeds Canada could go ahead.

“The big challenge is getting everyone to take off their individual hat and play with a team mindset. It’s often human nature to come to the table with a somewhat protective stance, but we got there and moved forward,” Sparry says.

“It took a couple of tries; mergers don’t always get done on the first go-around. But when you start to move outside of your little bubble, you realize we’re a global community. Remaining active within that international community will be very important as Seeds Canada moves forward.”

As the world begins turning the corner on the pandemic, the key to success will be a focus on innovation and being mindful to not get caught up in the daily turmoil of the business world, says Garth Hodges, vice president of BASF’s North American seed business.

“Twenty years ago, I had a manager named John Westridge. John taught me a very valuable lesson — at the time I thought it was the worst piece of advice, ever,” he says with a laugh.

That advice? If you chase two rabbits, you won’t catch either of them.

“I always thought if I can give John this long list of things, I can really impress him. But he kept saying, ‘What’s the most important one? What’s the one piece that’s really important?’ So, if I had to give advice, I think we as an industry have to choose where it is we want to focus. What’s the legacy that we as leaders are going to leave to the next generation?

Helping Government Keep Up

Turns out, the most exciting opportunities for the seed industry might also present the biggest challenges. As seed companies continue to innovate and move the needle on what crops can do, regulatory agencies haven’t always kept pace.

“Whenever you’re dealing with government and you’re working in an industry that is rapidly changing and discovery is happening on a monumental scale, it’s hard for government to keep up,” says Andy LaVigne, CEO of the American Seed Trade Association (ASTA). “Their natural reaction is to try to put the brakes on things in some form of policy or regulation and that’s what we fear most [in the seed industry].”

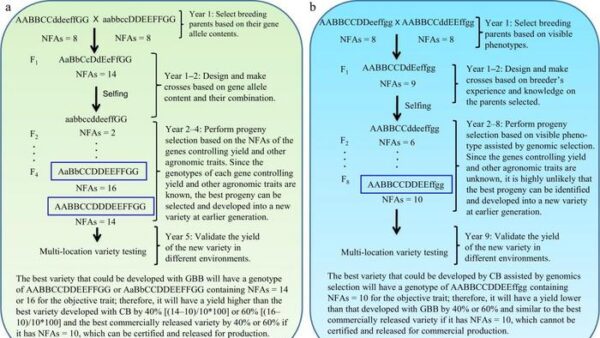

Scientists are making rapid improvements to the way farmers grow crops — so fast, in fact, regulatory bodies can’t keep up. From defining what new technologies are — such as CRISPR and other gene-editing techniques — to understanding what testing is required, the knowledge gap is only growing.

“Our challenge as an industry and as an association is, how do we communicate those changes while there’s not [yet] a reason to be concerned?” LaVigne says. “And how do we help people see this is a benefit?”

If a product is revolutionary, that challenge could become even more difficult in terms of only the breeding involved, but potential regulatory barriers that come along with new technologies. Hodges uses hybrid wheat as an example.

“There’s a good reason why hybrid wheat has been called a ‘stepchild’. It’s a challenge, with many conundrums and difficult steps along the way. We’ve been investing a lot in germplasm and trying to understand breeding different hybridization systems,” he says.

“Seed production has always been a big challenge in hybrid wheat, but it’s exciting because you’re actually breaking new ground and you’re doing something new.”

As cutting-edge breeding techniques become more advanced, expect more new ground to be broken — which will make the need for focus on behalf of industry leaders even more important.

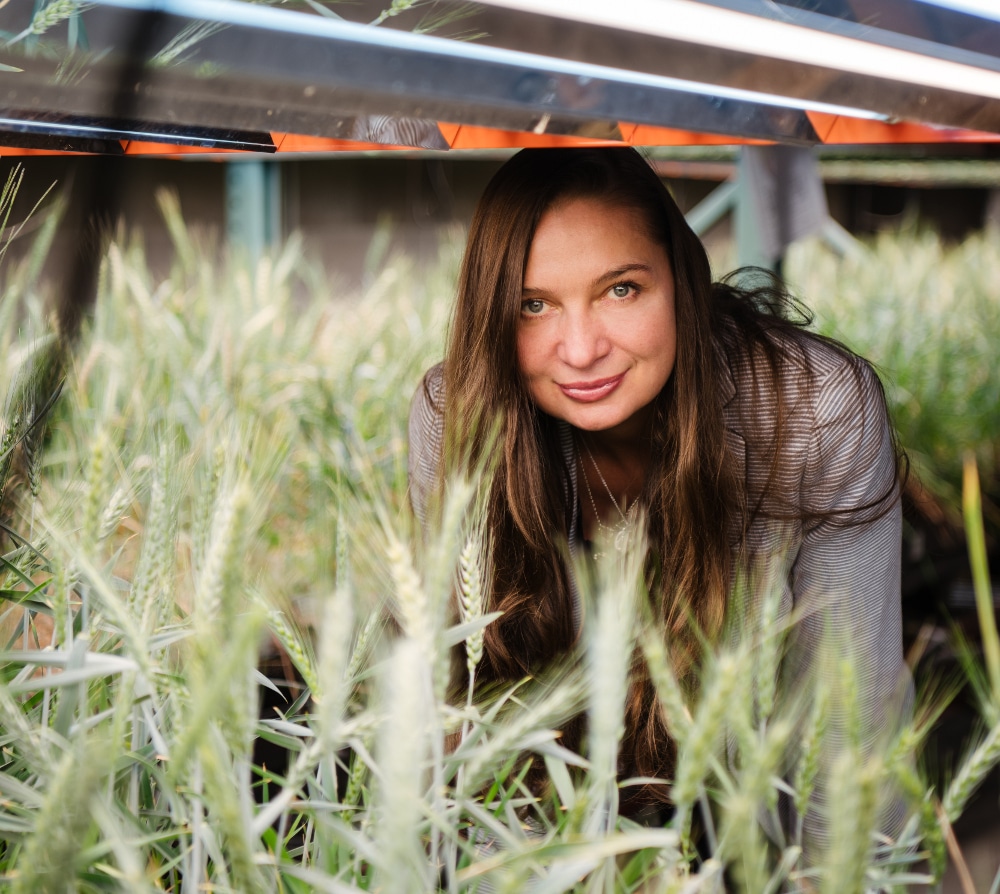

Colorado’s Limagrain Cereal Seeds (LCS) begins the second half of 2021 with a renewed focus, having completed a strategic restructuring, which CEO Tatiana Henry says frees up resources to enhance the company’s wheat breeding programs, which include a partnership with Limagrain Cereals Research Canada (LCRC), a joint venture between Limagrain and Canada’s Canterra Seeds.

“The integration of breeding tools like fast generation cycling, genomic selection and robust field selection means farmers will benefit from advancements in genetics and traits faster than ever before. We’re very proud to be able to use these tools to deliver maximum benefit farmers and the agricultural industry,” she adds.

Such innovation is a hallmark of the LCS and LCRC brands. LCRC has two wheat varieties — CS Daybreak and CS Accelerate — included in Canada’s Variety Use Agreement initiative, a value creation tool meant to increase plant breeding investment and innovation that’s the first of its kind in the country.

“One of our main breeding focuses is usable traits. We already have two major traits in our breeding program — a high-amylose trait, which offers high fiber content to consumers, and a Group 1 herbicide tolerant trade, which brings some flexibility in weed management for growers,” she says.

“We’re very proud of the work we do. With increasingly unpredictable growing conditions and consumer demands for healthy products, it’s a great time to work in wheat development.”

Despite enthusiasm for new technology, Hodges emphasizes that the industry will have to remain on guard to ensure public fears over new breeding technologies don’t win the day, as the ripple effects of those fears are often very widespread. Having worked within BASF’s Canadian business, he uses Canada as one example.

“Canada is really so dependent on its export markets that it’s almost as if the export markets are dictating what kind of technologies and innovations you can use. That’s problematic. Now, there are also macro challenges,” he says.

“We are so fragmented as an industry, but yet the challenge of societal and environmental acceptance is actually quite consolidated and unique. [Look at] the Green Deal in Europe. That’s something that the industry needs to think about.”

—with files from Alex Martin, Sonja Begemann and Marcel Bruins