Change is a known certainty about BREXIT. The tentacles of European policies will contract as British agriculture undergoes reform.

Businesses succeed where they adapt to market place changes. Economic, political, and technological changes are inevitable. Success stems from a management that is visionary, adopting strategic options with appropriate resources and a realistic risk analysis. Understanding risks and threats are too often ignored by senior executives leaving the company exposed to unexpected events. British Airways did not just have an IT failure, more importantly they had a management failure. Corporate complacency must be replaced by creative thinking and better engagement with customers. This applies as much to the plant breeding and seeds industry as it does any other.

Plant breeding is an activity; the actual business is managing and optimising the resultant intellectual property (IP). I want to emphasise management in this respect. “Is IP management a regular item on your Board Agenda?” is a key question that I ask CEOs of plant breeding companies. Responses invariably are of the nature “Yes of course, royalties are our life blood”. This belies the point of my question which was to question a company’s specific management of their IP. The response demonstrates however, that executive discussions often focus on royalty as an income stream tracking performance against budgets and forecasts. But what about the actual management of that income stream; is it efficient, effective and continually under review?

Plant breeders’ rights and patents are mechanisms of IP enshrined in law. These allow the innovator to structure how they may wish to be remunerated for their investment and rewarded for their innovation. Like a car, this cannot function without a knowledgeable driver. But here’s the rub. Probably the most undervalued aspect of IP within an organisation is the acquired knowledge that exists within it. It is the acquired knowledge within a business that makes IP work. That knowledge extends to understanding the market place, competitive value of the innovation and a raft of commercial and technical skills. The plant breeding industry excels in its technical innovation; sadly, however, when it comes to commercialisation, the seed industry lacks creative and progressive thinking to redress the widening imbalance in capturing the true value of new improved varieties.

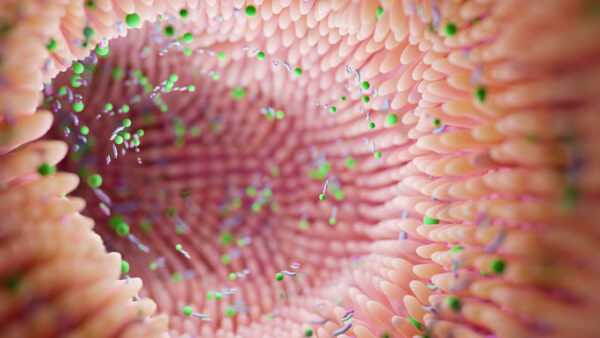

Seed is the transfer of innovation. Unlike other forms of IP, it is easily and cheaply reproducible. Moreover, it is reproduced by the user. Seed sellers will have it that the reason why a grower opts for using farm saved seed (FSS) is one of cost. But that is in total denial that the reason they opt to reuse the variety in the first place, is that the variety has proven its worthiness on the farm. Putting this another way, the unique genetics selected by the breeder is valued by the grower. It’s simple, if a variety underperforms they would not grow that variety. Seed and genetics are not the same. As an industry we should probably start to refer to farm saved genetics as opposed to farm saved seed.

Farmers have the privilege to use FSS and breeders are entitled to benefit through payment of “equitable remuneration” for the use of that variety. But what is equitable when, for the same genetics, a user of FSS is paying a rate half of that which is applied to a farmer growing certified seed? Taking into account collection fees, evasion and non-compliance, European plant breeding innovation is being starved of its just and equitable income by a discriminatory system. FSS is established on millions of hectares throughout Europe and last year for the first time in Germany there was more FSS winter wheat sown than certified. As the trend continues new business models and approaches are needed.

BREXIT negotiations will be complex. The devolved regions of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, supporting a narrow majority government will bring their influence to bear which in turn may lead to specific positions on agriculture. The National Farmers Union (NFU) continues to lobby for the rights to move FSS between holdings and with the changing dynamics and ownership of farms and accepting the effectiveness of the NFU lobby, I believe that the rationale against free movement will be hard to defend. I fear that this could legitimise the commercialisation of FSS. In bringing their case forward, the NFU will no doubt endeavour to provide reassurances that the equitable remuneration due will be paid by the user. But without evidence, the position of monitoring and controlling IP will be challenged and probably undermined. The FSS agreement between the British Society of Plant Breeders (BSPB) and NFU has delivered millions of pounds to breeders over the years, but we should not be wholly reliant on that agreement nor indeed should it restrict breeders to collectively or individually develop their own business models for IP management. Implicit to an evidence based approach will be robust terms and conditions of trade which allow for auditing, verification and monitoring of the breeder’s Rights under that sale.

Consumers are increasingly demanding product transparency, assurance and provenance. In the UK there are a number of successful value share contracts, some incorporating generic trademarks, which strengthens the organisation’s management of IP rights. However, we need to accelerate our evolution with a more dynamic approach to royalty collection and its management. This justifies and reinforces the need for the breeding industry to adopt an evidence based approach in managing IP. In the UK, less than 15,000 farmers produce 80 per cent of our arable output, yet we have a dysfunctional value change where the breeders have little direct contact with the users of their IP. However, the acceptance by UK oat and pulse growers, relatively minor crops in the UK, to enter into contractual royalty sharing agreements directly with breeders under a Royalty Area Collection Scheme, indicates an acceptance to change. This business model allows for direct knowledge exchange between the provider of the innovation (the breeder) and user (grower) where both share the common interest of optimising that variety’s performance on the farm. So not an end point royalty system, but a start point one.

With BREXIT and agricultural reforms on the horizon, the time is right for fresh, new and innovative approaches to IP management. However, as has proven the case in the past, the first challenge is where do we find the adventurist visionaries to champion the cause?