In a long-expected move, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences decided to award the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020 to Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, “for the development of a method for genome editing”. More precisely they got the prize for being the inventors of the CRISPR-CAS genome editing tool. ‘Finally’, ‘Well deserved’, ‘History was made’ and ‘Years in the making’ were some of the frequent terms to describe the decision.

And what’s more, with four women in total receiving a Nobel Prize in 2020, it marks an important step towards acknowledging the important role that women play in research and arts. The Nobel Prize started in 1901 and as of 2020, out of 930 winners, only 57 women have won the Nobel Prize (6 per cent).

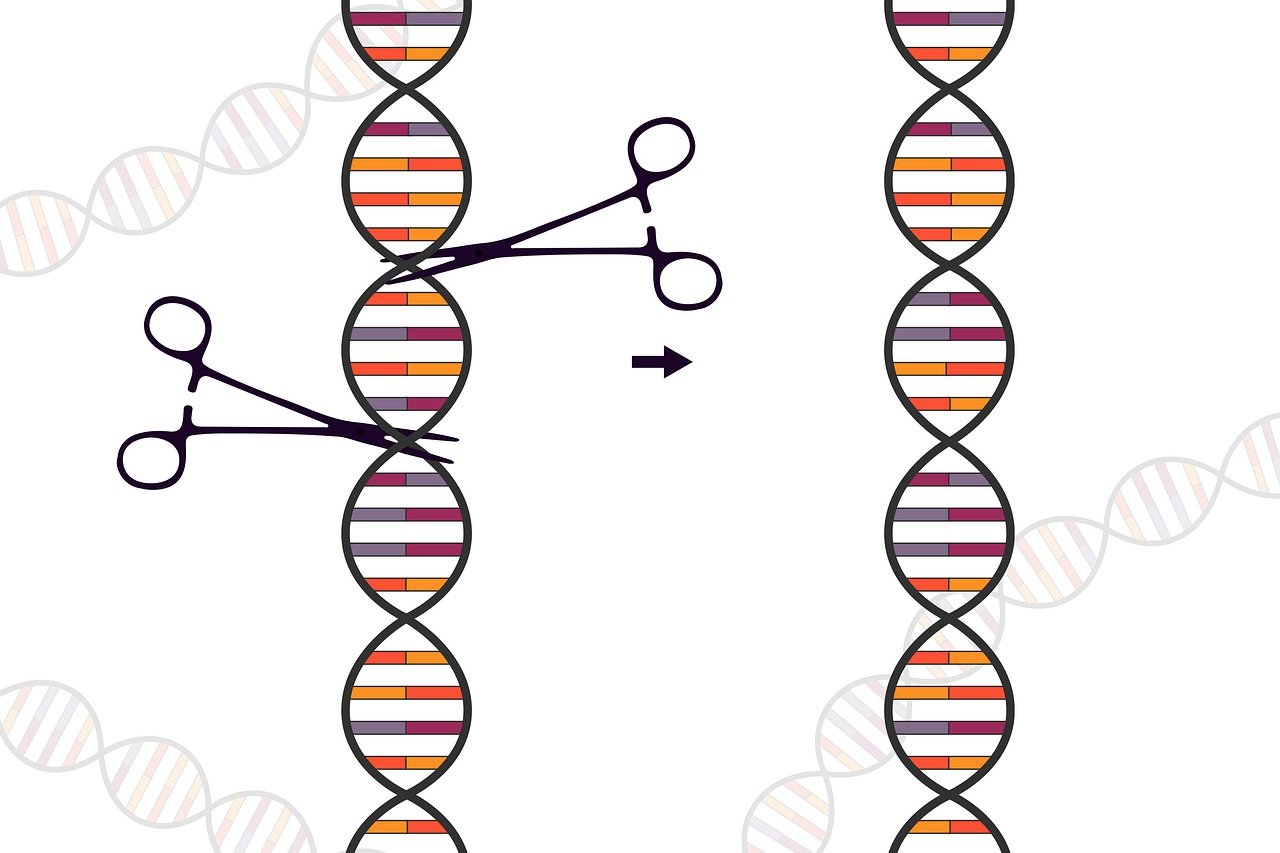

CRISPR is actually the defence mechanism of bacteria against virus attacks. A lot of scientists have deciphered pieces of the system and Charpentier, who is director of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens, Berlin, Germany and Doudna, who is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, U.S., discovered that with the help of CRISPR-CAS it was possible to change the DNA of animals, plants and microorganisms with extremely high precision.

Their invention already has had a revolutionary impact on life sciences, despite the fact that the tool is less than a decade old. Adding to the revolutionary impact of the invention, it is good to realize that most Nobel Prizes are based on research that spans two, three, or more decades. Just imagine that in 2011, there were less than 100 published papers on CRISPR. And this year (2020), that number had risen to over 35,000! Doudna and Charpentier published their ground-breaking scientific publication on CRISPR in 2012 and since then it has received more than 6,000 citations already. There are only 700 scientific papers out of 50 million, published since 1970, have received that many.

CRISPR-CAS has opened up avenues to more efficient plant breeding and researchers have already been able to develop the first crops that are able to better withstand climate threats, such as drought tolerance, as well as new pests and diseases. But CRISPR is also contributing to new cancer therapies, and many important discoveries in basic research.

Not only the academic world jumped on the invention. Many new companies were created to develop products with the help of this technique, from therapies for genetic diseases to engineered crops. And particularly relevant in our pandemic times: scientists have even developed a CRISPR-based test to detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

And why is this all so important? Elsewhere in this issue you will read more about the EU Green Deal and its Farm to Fork Strategy. These policies set a number of goals to be reached by 2030, such as a reduction by 50% of the use and risk of chemical pesticides; a reduction by 50% of the use of more hazardous pesticides; a reduction of nutrient losses by at least 50%, while ensuring no deterioration in soil fertility; a reduction of fertilizer use by at least 20%; and 25% of total farmland to be organically farmed. And these very ambitious goals (some say ‘unrealistic’), can’t be achieved without the tremendous and ongoing efforts of the plant breeding and seed sector. These sectors will prove to be crucial going forward and achieving those goals. But plant breeding is a long process, and on average it takes six to15 years to create a new variety. With CRISPR we could achieve the same result much faster and with more precision and accuracy.

The trouble is that since the infamous decision in July 2018 by the European Court of Justice (ECJ), Europe is faced with the fact that the CRISPR technique (and several other very promising ones) falls within the legal definition of genetic modification. The costs of developing and getting approval for a genetically modified plant variety is estimated at well over 100 million €. So, the ECJ decision places CRISPR fully out of reach for many small and medium sized plant breeding companies, as well as for the public sector plant breeders and only the largest companies would have the resources to benefit from CRISPR’s full potential.

Let’s hope that the Nobel Prize on CRISPR will provide sufficient recognition and awareness to push for a science-based decision process and speed up the regulatory discussion on the use of this technique and other plant breeding innovations. If we want to make a serious effort at achieving the Farm to Fork goals, we will need CRISPR and other new tools for the EU plant breeders so they can fully explore its great potential to the benefit of us all.