The seed industry has grown accustomed to feisty competition among trait providers, but now they are about to see more fierce competition in the ag-retail sector.

Large players in the retail sector are growing fast and have plans to get bigger. That was the thrust of a speech by Tray Thomas of The Context Network at an Illinois Foundation Seed, Inc. event last December. “I can see a battle line being drawn between large co-ops and Agrium—and both are interested in seed,” he says.

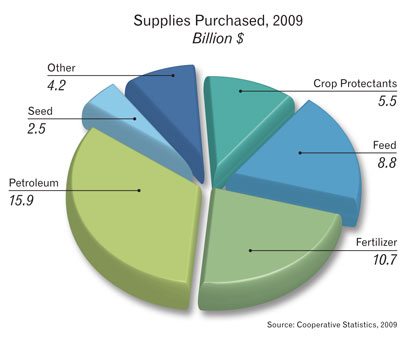

Thomas and The Context Network have studied recent changes in the ag-retail sector. Co-operatives have been declining in number, but the volume of business for those remaining is up significantly. They are unique competitors who each have a complex business mix, which typically includes a wide array of products representing various proportions of their businesses. For instance, on average $16 billion is petroleum, $11 billion is fertilizer and just $4 billion is seed.

At the same time, consolidation is also affecting privately held ag-retail chains. Most notably, Agrium is growing at a rapid rate, investing heavily in channel acquisitions. The investment in distribution capacity is just one part of the company’s plan. Its model is to offer wholesale, retail and private label products from its vast fertilizer infrastructure. Considering fertilizer is growers’ largest expense, Agrium has a considerable advantage in the supply chain, with its capacity to offer discounts.

Agrium, co-ops and traditional seed companies are likely to have very different sales forces, with completely different styles. For Thomas, the key to success, no matter what the sales force, is the ability to successfully assimilate the mass of information farmers face. Farmers are awash in details on seed varieties. What they need is a mechanism with which to compare apples-to-apples, and understand which varieties are the good performers, well-suited to their specific farming needs.

Once, seed distributors had an innate advantage because they had access to varieties and details on their performance. Now, Thomas asks, “Is it really enough to just have seed information? Others have information on seed, fertilizer, crop protection and so on.”

Retailers, who have the capacity to help farmers with active information-gathering and evaluation of alternatives, have a critical influence on purchasing decisions. “There is value in problem solving for growers,” says Thomas.

The fact is that people have been talking about the shift between large-scale, mid-size and lifestyle farm operations for years. The concepts may be well recognized, but the inputs business remains mediocre at segmenting these markets and serving them well. Each market can be viable, but retailers are unlikely to successfully meet all the needs of each category. The ability to provide farmers with synthesized (which means short), dynamic (which means comparative) analysis will win market share.

Horticulturalization

That market share is likely to become more worthwhile as field crops are “horticulturalized”—a term Thomas coins to capture the added value associated with seed. Increasingly, the care once given to every precious vegetable seed through application of treatments and enhancers is now being used on field crops. Each unique stack of traits, every bit of underlying germplasm, needs to be given the maximum start. The culture of “value” is changing the interaction in seed.

The result will be a further proliferation of available products. “SKU management will be paramount,” warns Thomas. The ability to administer this and mitigate inventory risk is increasingly a factor in seed retailing success.

Thomas also cautions that price pressure is likely to grow. Even while seed is being treated as precious, increased competition in the retail sector is likely to continue driving down prices. Not only that, he predicts the next generation of traits for drought-tolerance and other stresses will make it harder to capture value. Each product’s complexity and the nuances of when it works will require an extra level of customer trust and support. For instance, when is it a drought? When is it just dry? And if a crop is already in crisis due to lack of water, how much performance is a reasonable expectation? These are tough questions that could come at tough times in a farmer’s growing cycle. Are seed sellers ready to answer them?

The answers may not be easy. Nor is the introspection that Thomas prescribes. He encourages every seed retailer to look hard at its ability to segment the market, establish trust with those farmers, and provide the information each segment needs and the service the market requires. After all that soul-searching, seed sellers still need to compete on price too. It could all mean some members of the channel get tuned out. Robynne M. Anderson