Grapevines, the foundation of a global industry worth over $300 billion, are under siege from an ancient and persistent enemy: downy mildew. Caused by the water mold Plasmopara viticola, this microscopic invader thrives in humid climates, infiltrating leaves and spreading rapidly, leaving behind yellowing blotches and the telltale cottony spores that spell trouble for vintners around the world.

Traditionally, chemical fungicides have served as the first line of defense — but at a steep cost. Overreliance on these treatments has led to resistant strains of the pathogen, environmental contamination, and mounting pressure from consumers demanding organic and sustainable alternatives.

Now, a new study is offering hope in the form of two unlikely allies: an extract from a brown seaweed called Ascophyllum nodosum and a soil-dwelling bacterium known as Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0.

“Together, they may represent a paradigm shift in sustainable disease control,” says study co-author Balakrishnan Prithiviraj, plant stress physiology research chair at Dalhousie University.

Biology Over Chemistry

Ascophyllum nodosum, harvested from cold North Atlantic waters, is already prized in agriculture for its biostimulant properties. Rich in natural compounds like alginates, fucoidans, and laminarin, it helps plants manage stress, absorb nutrients, and activate immune responses. Pseudomonas fluorescens, meanwhile, is a well-studied rhizobacterium capable of outcompeting pathogens, triggering systemic resistance in plants, and producing antifungal compounds.

Individually, both have shown promise in defending crops. But their combined application — especially against grapevine downy mildew — has remained largely unexplored.

This study changes that.

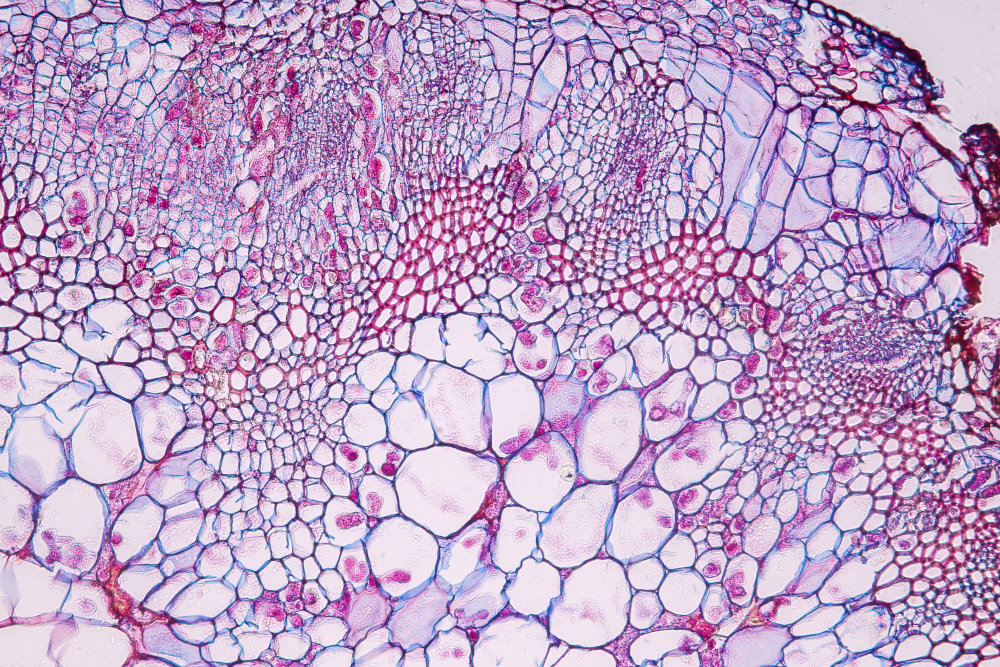

Researchers applied A. nodosum and P. fluorescens, both separately and together, to grape leaves in the lab and in greenhouse trials. The results were striking. While individual treatments reduced spore development and disease symptoms, the combined treatment consistently outperformed both.

In vitro, the dual application cut down spore production by 66%, zoospores by over 90%, and empty sporangia — the spent structures left behind after infection — by up to 69%. In greenhouse trials, the incidence of downy mildew dropped to just 22% in treated plants, compared to 70% in untreated controls.

More than just blocking infection, the bacterial duo seemed to prime the grapevines for defense.

A Biochemical Battle Plan

When plants detect an invader, they launch a complex defense involving a battery of enzymes, antioxidants, and antimicrobial compounds. The combined application of A. nodosum and P. fluorescens significantly boosted the activity of key defense enzymes: phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), peroxidase (PO), and polyphenol oxidase (PPO). These enzymes contribute to lignin production (which fortifies plant cell walls), oxidative bursts (which damage invaders), and the synthesis of phenolic compounds—natural antimicrobials.

“Importantly, the treatments also increased levels of hydrogen peroxide, a reactive oxygen species that serves both as a signaling molecule and a weapon against pathogens,” Prithiviraj says. This biochemical cascade creates what plant scientists call a “primed” state—a heightened readiness to fend off infection quickly and forcefully.

The Genetic Signal

The team also observed upregulation of several key genes involved in plant defense — most notably those linked to the jasmonic acid (JA) pathway, which is typically associated with defense against insect pests and necrotrophic fungi. Among the genes activated were LOX9, PR4, CHI, OSM1, and two germin-like proteins, GLP2 and GLP7.

Surprisingly, genes associated with the salicylic acid (SA) pathway — usually dominant in defense against biotrophic pathogens like P. viticola — remained unchanged. This suggests that the ANE and CHA0 combination might be activating an alternate or complementary route to resistance, one that could be more robust or less prone to suppression by the pathogen.

Rethinking Pathogen Defense

“The classical thinking has been that biotrophic pathogens like downy mildew are best controlled through salicylic acid–mediated responses,” Prithiviraj notes. “But our data suggests the JA pathway can play a larger role than previously thought—particularly when primed by natural compounds like those found in ANE and CHA0.”

This is not entirely without precedent. Other studies have hinted at jasmonic acid’s role in grapevine resistance, but the level of synergy observed here between ANE and CHA0—at both the biochemical and molecular levels—is unique.

Toward Sustainable Viticulture

For winemakers and grape producers, these findings could pave the way toward less chemically intensive farming. As climate change increases disease pressure and consumer demand for organic wines rises, biologicals like ANE and CHA0 could offer a scalable solution—if further field trials confirm the results.

The use of a seaweed extract and a rhizobacterium may seem like a return to simpler times. But as this research shows, it’s anything but simple. These organisms are activating sophisticated plant immune responses honed over millions of years of co-evolution.

Inside the Downy Mildew Defense Network

From vine to romaine, an ancient enemy is getting a modern reckoning. Across North America, scientists are launching a coordinated attack on one of agriculture’s most elusive threats: downy mildew.

The Grape Genome Breakthrough – Cornell University. Nestled in New York’s Finger Lakes, researchers at Cornell have unearthed a naturally occurring resistance gene in grapes. It’s a discovery that could rewrite the playbook for fighting vineyard downy mildew — one of the wine industry’s most persistent foes. With support from the USDA’s Grape Genetics Research Unit, breeders are now working to embed this resistance into future grape varieties, reducing fungicide use and building resilience into the very DNA of the vine.

Lettuce Fight Back – UC Davis & USDA-ARS. In the heart of California’s salad bowl, researchers at UC Davis are diving deep into the lettuce genome. Their goal? To engineer cultivars that can shrug off downy mildew without the need for constant chemical defenses. Meanwhile, at USDA-ARS in Salinas, Beiquan Mou has released new green leaf, red leaf, and romaine lines resistant to not just downy mildew — but also corky root and the dreaded leafminer. For growers, it’s a sustainable triple threat that could redefine how leafy greens are bred and grown.