In a major scientific breakthrough, researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have successfully revived fungal specimens collected over 80 years ago, shedding new light on how industrial agriculture has reshaped the microbial ecosystems that underpin global food production.

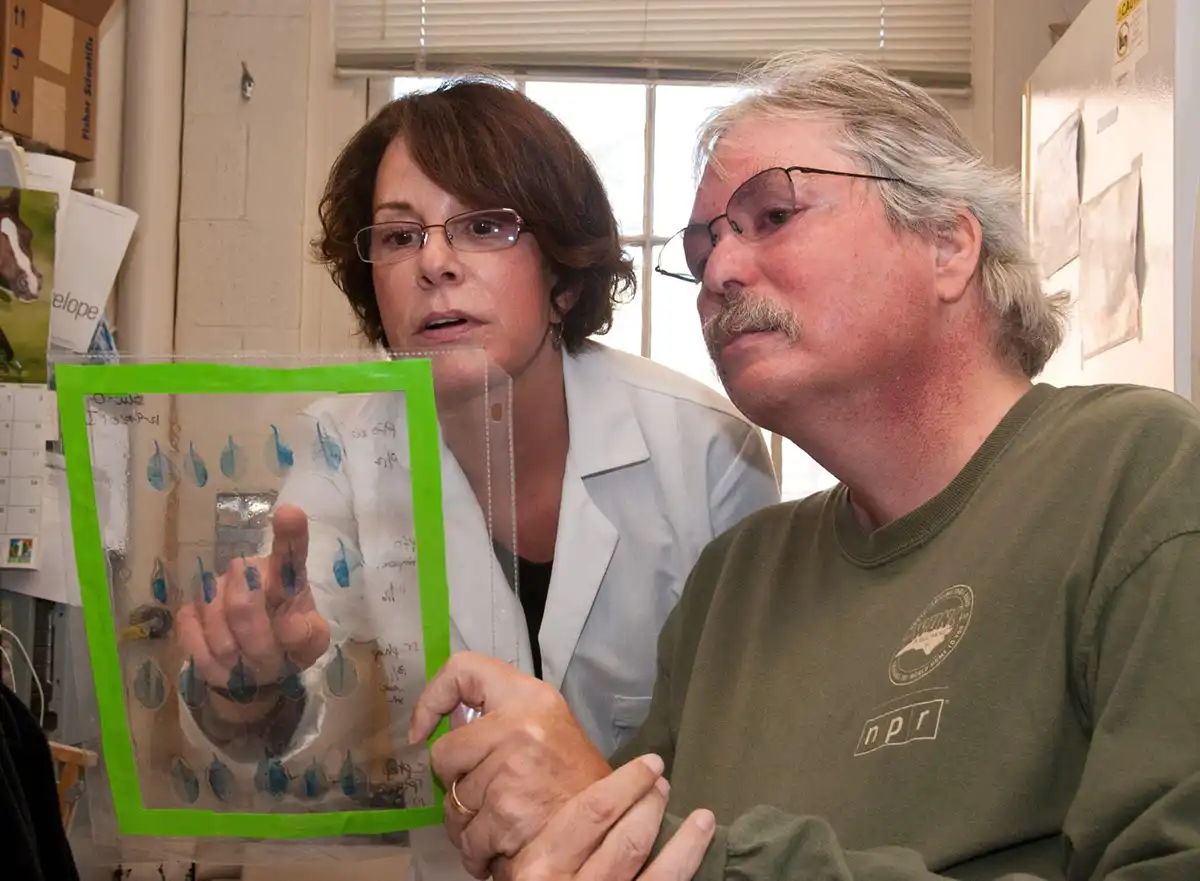

Published in iScience, the study was led by Dr. Dagan Sade under the supervision of Professor Gila Kahila of the Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, in collaboration with Tel Aviv University, Ben-Gurion University, and Israel’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. The focus: Botrytis cinerea, the plant pathogen behind gray mold disease, which affects more than 200 crop species and causes billions in annual agricultural losses, according to a press release.

To explore how this fungus has changed over time, the team revived two B. cinerea strains preserved since the early 1940s in the Hebrew University’s National Natural History Collection — well before the widespread use of synthetic fertilizers and fungicides that defined the Green Revolution.

Using state-of-the-art tools including whole-genome sequencing, transcriptomics (gene expression), and metabolomics (chemical profiling), researchers compared the revived strains with modern lab versions. The results were striking:

- Reduced signs of fungicide resistance, a feature that has become prominent in modern strains due to heavy chemical use;

- Differences in pathogenicity, with some traits suggesting the historical fungi were less specialized and aggressive than their contemporary counterparts;

- Adaptations to different environmental conditions, including pH tolerance and host specificity.

“These fungi have been quietly evolving in response to everything we’ve done in agriculture over the past 80 years,” said the researchers. “By comparing ancient and modern strains, we can measure the biological cost of human intervention — and learn how to do better.”

A Window into the Agricultural Past — and Future

The research carries broad implications. As climate change, pesticide overuse, and soil degradation intensify, understanding how plant pathogens respond to human-driven change is essential for building more sustainable farming systems. Reviving historical microorganisms offers a critical baseline — helping scientists separate natural evolutionary shifts from those triggered by modern agricultural practices.

“Natural history collections have always been valuable for taxonomy and museum science,” said the researchers. “But this work shows they are also dynamic resources for modern biology. They allow us to ‘rewind’ microbial evolution and anticipate future trends in plant disease.”

The study also supports global efforts to predict and manage plant disease outbreaks. By uncovering how pathogens once adapted to environmental change, researchers can better model future risks and develop crop protection strategies that reduce dependence on chemical treatments — limiting ecological damage and slowing resistance.

Reviving More Than Specimens

This project reflects a growing scientific movement: using biological archives to tackle today’s most urgent challenges. From climate change to antibiotic resistance and biodiversity loss, many modern problems demand historical perspective.

“This work is a perfect example of how past and future can intersect through science,” said the researchers. “We brought something back to life not for nostalgia, but to help build a more sustainable agricultural system.”

The project drew on expertise in genomics, microbiology, and metabolomics. The team hopes their findings will inspire other institutions to recognize the untapped potential in their biological collections — and embrace interdisciplinary approaches to solving global food and environmental crises.