Every growing season, farming generates large amounts of crop residues such as straw, husks, and stalks. These are usually managed through burning, plowing back into fields, feeding to livestock, or composting. However, these practices release greenhouse gases (GHGs) including methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N₂O), and carbon dioxide (CO₂), contributing to climate change and posing risks to long-term food security.

A recent study by researchers from the Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, suggests that biochar — a charcoal-like substance made by heating crop residues under low-oxygen conditions (pyrolysis) — can provide a more sustainable alternative.

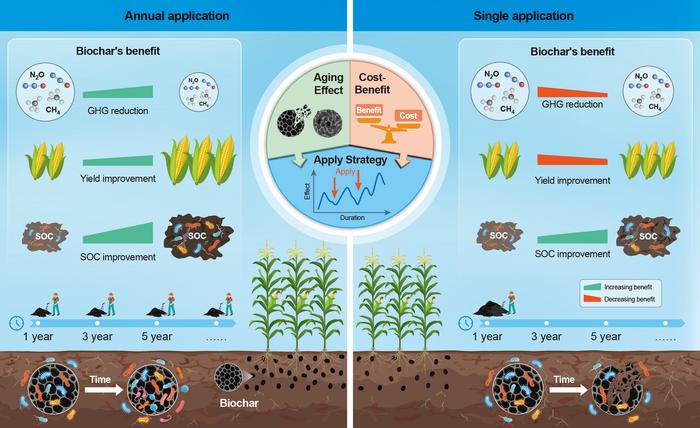

The team, led by Profs. Yan Xiaoyuan and Xia Longlong, found that applying biochar to farmland offers lasting benefits for both crop production and climate mitigation. In particular, repeated annual applications enhanced crop yields, improved soil quality, and reduced GHG emissions over the long term, according to a press release.

The study drew on data from 438 field experiments, including multi-year records from 29 long-term trials. Results published in PNAS show that annual biochar application for four years or more increased crop yields globally by an average of 10.8%, reduced CH₄ emissions by 13.5% and N₂O emissions by 21.4% and boosted soil organic carbon (SOC) content by 52.5%.

Although the effects of a single biochar application diminished over time due to aging, it still produced measurable benefits in terms of yield, SOC, and GHG reduction, though with a gradual decline in strength.

“We wondered how significant biochar’s potential could be for carbon sequestration and emission reduction in global farmlands under long-term application,” said Jingrui, first author of the study and a PhD student from ISSCAS.

Using current data on straw use and biochar management, the researchers estimated that converting 70% of crop straw into biochar for farmland could increase global grain yields by 190 million tons per year. It could also enhance carbon dioxide removal (CDR) by 2.01 Pg CO₂-eq annually—equivalent to about 30% of China’s average annual grain production between 2018 and 2021.

After factoring in greenhouse gas emissions from biochar production (0.25 tons of CO₂ per ton of biochar), the net CDR potential remains 1.84 Pg CO₂-eq annually, enough to offset about 4.6% of global fossil fuel CO₂ emissions.

The study suggests that applying biochar at multi-year intervals or alternating it with fallow periods could sustain its benefits in a cost-effective way while reducing risks. More field trials across different soil types, climates, and cropping systems are needed to refine application strategies, including the most effective frequencies and rates.

The researchers note that while tailored, periodic application of biochar could reduce costs and deliver long-term advantages, the upfront investment may discourage adoption among risk-averse farmers.

“Since farmers are unlikely to increase input costs unless there is strong evidence it pays off, large-scale demonstration trials in major grain-producing regions such as the North China Plain and the U.S. Corn Belt are essential to prove both economic and environmental benefits,” said Prof. Yan.

A cost-benefit analysis by the research team found that higher crop yields and reduced greenhouse gas emissions could cover roughly 81% of biochar production costs, with even greater savings when reduced nitrogen losses are considered. The researchers suggest that government subsidies and supportive policies will be important for expanding biochar use and maximizing its potential for sustainable agriculture and climate mitigation.