UC Davis researchers are advancing wheat by removing its most reactive gluten proteins and maintaining dough strength, unlocking new potential for performance and health.

For decades, gluten has been central to wheat’s value in the marketplace — the driver of dough strength, elasticity and reliable performance in the kitchen. But for people with celiac disease, those same proteins present health challenges. As consumer needs evolve, the grain industry is increasingly being asked to consider traits beyond yield and baking quality.

At the University of California, Davis, plant biologists are taking on this challenge. Their work focuses on removing the most reactive gluten components while preserving the traits that enable wheat to grow and bake well. The goal is simple: make wheat safer without compromising what makes it wheat.

Proof in the Flour

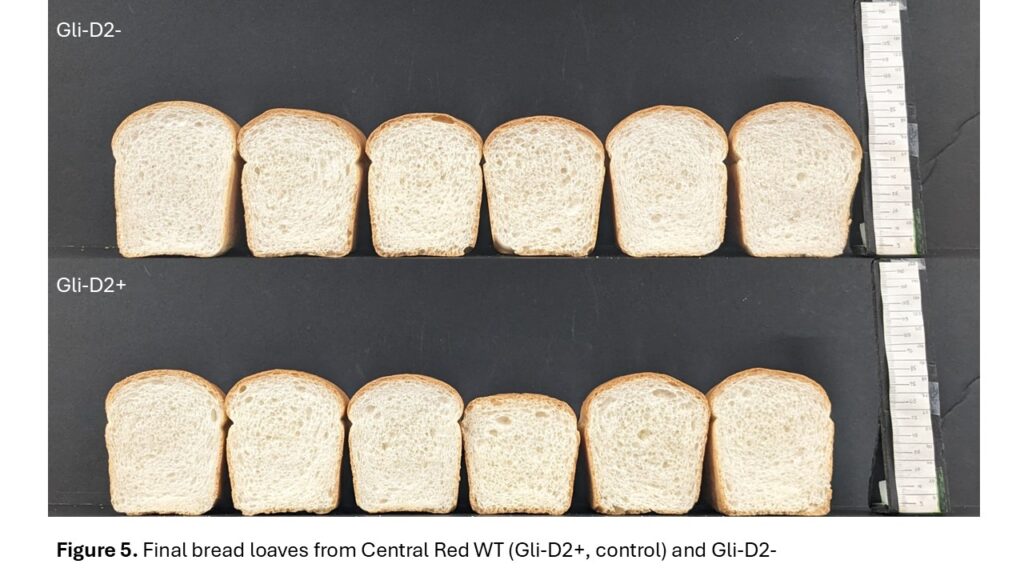

The study targets a specific cluster of alpha-gliadin genes, the gluten fractions most closely associated with triggering severe immune responses. Using gamma radiation to delete these sequences, the UC Davis team produced experimental lines that still had strong dough performance but fewer of the problematic proteins.

“We actually got improved bread-making quality, which is not expected, considering gluten is a main component of making bread,” remarks Maria Rottersman, the study’s lead author and UC Davis doctoral student in plant biology. “And these proteins are some of the worst triggers for most [people with] celiac disease, so this is a win-win in terms of finding a genetic modification that benefits both producers and consumers.”

The new varieties are not GMOs. The UC Davis team, led by Jorge Dubrovsky, produced the deleted-gene varieties through traditional breeding. After generating seed and testing flour and dough performance at the California Wheat Commission’s quality lab, they deposited the validated lines into the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Germplasm Resources Information Network so breeders can access them.

But for Rottersman, turning lab data into something tangible — fresh-baked bread made from the edited wheat — was a special moment.

“I spend so much time looking at gene sequences or working with DNA I can’t see, but having something physical in my hands — something you can bake, eat, touch and see — was extremely rewarding.”

Funding the Space Between Food and Health

The edited wheat isn’t celiac-safe, but the study’s findings are an essential first step.

Approximately 1% of the American population lives with celiac disease, and Rottersman notes that 30 to 40% have genes that make them more likely to develop it later in life.

“Having some varieties that have a lower amount of these proteins that trigger the disease means that we’re delaying the onset for those who don’t know they’re at risk,” she says.

Creating safer wheat also requires partners who see the bigger picture. Funding for the research came from the Celiac Disease Foundation, USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR).

Marilyn Geller, chief executive officer of the Celiac Disease Foundation, stresses that the disease is not a lifestyle choice, but a medically necessary diet. With gluten present in 80% of our food supply and no therapeutic drug currently available to treat celiac disease, Geller says patients must navigate a world where every bite carries risk.

“A safer wheat would be transformative for the celiac community,” she says. “Imagine being able to go to a restaurant and not worry about cross-contact with gluten because everything is made from safer wheat. That kind of freedom is as huge as it gets.”

The Celiac Disease Foundation provided the initial funding for the study, recognizing it as a needed counterbalance to drug research.

“We’re investing in patient recruitment for drugs, but we’re also hedging our bets and

seeing what we can do with the wheat,” Geller says. “Either way, we get something to market that will be better for people with celiac disease and wheat allergies.”

Connecting Different Parts of the Food Chain

FFAR scientific program director Constance Gewa echoes Geller’s urgency. She explains that gluten reactions can so severely damage the digestive system that patients have trouble absorbing nutrients. Many develop anemia or other nutrient deficiencies, made worse by the strict diet they must follow.

Wheat varieties that reduce these immune responses could help break this cycle and support healthier diets without giving up traditional foods.

Gewa says FFAR backed the gluten-editing project because it aligns with their mandate and impact goals. Established in the 2014 Farm Bill to increase public agricultural research investments, fill knowledge gaps and complement USDA’s research agenda, FFAR prioritizes work that can improve human health through food and agricultural innovation.

Gewa says they fund research with potential impact, looking for scientific rigor, strong partnerships, and a clear pathway to real-world use — all qualities they saw in this study.

In addition, she says that FFAR evaluates research for how well it connects different parts of the food system.

“If you think about the functionality of the food system, it’s not just about producing food,” she states. “It’s a whole chain — from pre-breeding all the way to human health — and that system must function well. This study is a good example of work that connects those pieces.”

Science Moves Faster When Sectors Work Together

Everyone involved in this project points to teamwork as the reason it is moving forward.

For the Celiac Disease Foundation, collaboration is central. Geller says the foundation has been “thrilled to be at the table” with other entities that recognize the importance of the work.

She praises the UC Davis team for driving strong results for an early-stage project, crediting them for what they have done in a short period with few research dollars.

Inside the lab, the project brought Rottersman into conversations with experts far beyond her discipline. She says the work connected her with gastroenterologists and immunologists that she wouldn’t have met otherwise, expanding the scope of the research.

FFAR invests in research with long-term, practical impact, actively evaluating a project’s collaborative framework — who is involved, how they will contribute, and whether the work positions everyone for success.

“Research does not happen in a vacuum,” Gewa says. “Research needs money, research needs ideas, research needs partners and stakeholders in place.”

From Public Germplasm to Commercial Fields

The edited lines are still experimental, but interest is growing. Rottersman says artisanal bakers, millers, and farm-to-fork operations are already asking about the work. UC Davis breeders are now moving the deletion into a commercial California wheat variety called Central Red, an early step toward wider use. The germplasm is already public, and Rottersman understands that the move toward commercialization is close.

For stakeholders like Geller, the fast progress at UC Davis is encouraging. But they also know that turning early discoveries into real-world change takes time.

“Progress is always incremental — one step forward, two steps back sometimes, she says. “But that’s why we exist. Our job is to keep the optimism alive, to invest in the science and to show our patients what’s possible.”