For the winner of this year’s World Food Prize, the secret to lifting millions of smallholder African farmers out of poverty has been in giving them access to better quality seed.

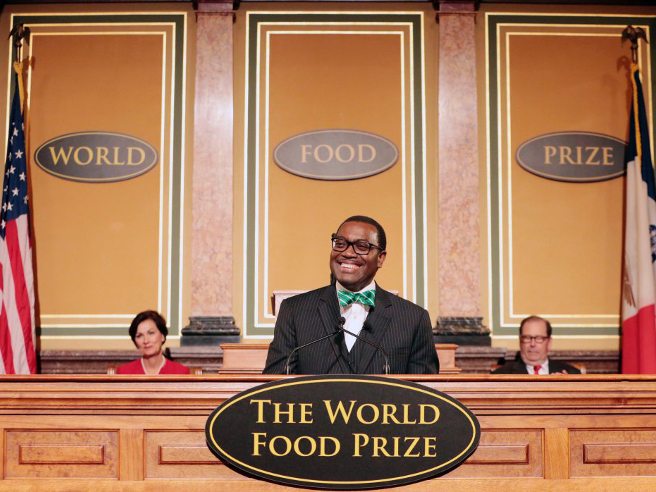

Akinwumi Ayodeji Adesina, president of the African Development Bank, has been heralded as “Africa’s Norman Borlaug,” and for the past 25 years has crafted policy that’s helped provide support for millions of farmers across the continent. As a result, he was honoured in October with the World Food Prize, given annually to recognize significant achievements in feeding the world.

The selection of Adesina as the 2017 World Food Prize Laureate reflects both his breakthrough achievements as Nigeria’s agriculture minister and his critical role in the development of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), said Ambassador Kenneth Quinn, president of the World Food Prize Foundation.

“It also gives further impetus to his profound vision for enhancing nutrition, uplifting smallholder farmers and inspiring the next generation of Africans as they confront the challenges of the 21st century.”

In his formal address delivered at the World Food Prize Laureate luncheon in Des Moines, Iowa, Oct. 20, Adesina highlighted the crucial role better access to quality seed has had in his quest to improve conditions for farmers throughout Africa.

Born in 1960 in Ibadan, Nigeria, Adesina grew up in a one-room house without electricity or plumbing and slept side-by-side with his brothers on mats on the floor. Although his grandfather and father worked as farm labourers, his father was eventually able to receive some education as a teenager, which led to employment as a civil servant and provided the means to send his own sons to school.

Adesina went on to earn both his master’s and Ph.D in agricultural economics at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana.

His goal was to return to Africa to help smallholder farmers increase crop production and improve their livelihoods. To that end, he accepted a post-doctoral fellowship at the Rockefeller Foundation in 1988. The Rockefeller fellowship started him on an Africa-based 10-year career within the CGIAR system.

“I realized millions of farmers were unable to access improved seed and fertilizers because rural input markets were poorly developed or absent in most cases. It was easier to find soda pop in rural Africa than it was to find high-performing sorghum varieties,” Adesina said.

An early initiative of Adesina’s was his development of small agri-retailers throughout the continent. Working with international and local NGOs, he helped design a selection, training and certification process that converted small village-based shops selling sodas and soap into small agri-retailers who sold seeds, fertilizers and other inputs and advised farmers on their proper use.

With the rapid growth of mobile phones in Africa, opportunities were opened for farmers to receive market and other information directly. Adesina was able to help them obtain the inputs they needed through a first-of-its-kind Electronic Wallet (E-Wallet) system, which provided subsidized electronic vouchers directly to the farmers’ mobile phones, vouchers that were then used like cash to purchase fertilizer and seeds directly from agri-retailers. This led to a revolution in accessibility to the basic tools that farmers needed in order to significantly increase the quality and quantity of the crops they planted.

Within the first four years of instituting the E-Wallet system, the lives of 14.5 million farmers and their families had been dramatically transformed. Among these were 2.5 million women farmers who were reached and empowered by having mobile phones. The efficient delivery of inputs to farmers combined with other interventions saw a sharp growth of $2 billion in five value chains of cassava, rice, sorghum, maize and cotton.

“Today, we have tissue culture bananas that yield 40 tons per hectare, pro-vitamin A cassava and water efficient maize,” Adesina said. “The new agriculture gospel is simple: to lift millions out of poverty, agriculture must be treated as a business. Doing so gives hope for economic prosperity for Africa.”

His hope is that rural African communities, where agriculture is one of the biggest sources of work, will be strengthened in an era where manufacturing jobs commonly attract people to large urban centers.

Adesina committed his $250,000 World Food Prize award to set up a fund fully dedicated to providing financing for the youth of Africa to get involved in agriculture.

—with files from the World Food Prize Foundation