Two young scientists are quietly rewriting the rules of plant breeding — not in the lab, but in the way they think about resilience, flavour, and the future of food.

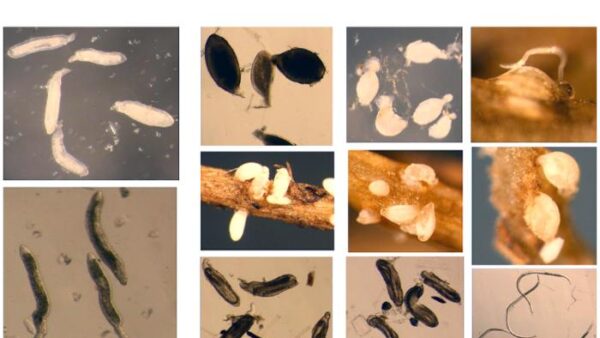

The battle begins where most people never look: inside a seed. Microscopic, quiet, and unyielding, it’s here that science meets survival. And for researchers Hannah Jeffery (a postdoc at Texas A&M University) and Gurminder Singh (PhD candidate at North Dakota State University) — a mentor-mentee duo navigating the shifting terrain of plant genetics — the seed is not just a symbol of life, but a data point, a puzzle, a promise.

As a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Advancing Health Through Agriculture at Texas A&M AgriLife, Jeffery is excited to be working alongside Dr. Tim Paape (USDA-ARS) on enhancing the nutritional value of locally adapted maize and sorghum lines. Prior to working with Dr. Paape, she was a Ph.D. student working with Dr. Karen Cichy (USDA-ARS) in the Department of Plant, Soil, and Microbial Sciences at Michigan State University. While there, she characterized the genetic control of cooking time in dry beans landraces and some elite germplasm. This enabled her to develop genetic markers for cooking time that may improve the consumer quality of locally adapted dry bean germplasm.

Singh is looking at wheat resistance to tan spot disease. He works in the Wheat Molecular Genetics Lab at USDA-ARS.

In a conversation that starts with beans and wheat and ends with a reimagined food system, the two plant scientists peel back the husk of what it takes to make crops that endure. Crops that taste good. Crops that don’t just grow — but matter, Jeffery says.

It’s a philosophy shaped as much by failure as it is by innovation.

Cooking Time and Survival: What Beans Can Teach Us About Stress

One of Jeffery’s earliest questions wasn’t about plant height or yield — it was about dinner.

“When you’re breeding for dry beans, people care about how long they take to cook,” she says. “Some varieties take forever — and we think the compounds that make them hard to cook might also help them survive drought or disease.”

That simple observation led to a much deeper inquiry: could culinary inconvenience be a sign of genetic armor?

“We’re testing that now,” she says. “The hypothesis is that those tough-to-cook traits could be linked to stress tolerance — but that’s still a hunch.”

The Tug-of-War Between Wild and Useful

For Singh, the journey winds through the thickets of wheat’s wild ancestry.

He works on a disease that modern cultivars are vulnerable to — but for which resistance already exists in wheat’s wild relatives. The problem? Getting that resistance back without dragging along unwanted baggage.

It’s the classic breeder’s paradox: the genetic gold is there, but the mine is unstable.

The Tools Are Sharp. The Questions Are Sharper.

Both Jeffery and Singh work at the cutting edge of plant science — using whole genome sequencing, CRISPR gene editing, and bioinformatics tools that can predict, model, and map traits with breathtaking precision.

But even with all that tech, there’s one thing the data still can’t tell them, Singh says.

Jeffery spent much of her PhD studying landraces — ancient crop varieties passed down through generations. But their future is murky. The plants may never make it to market, but the genes inside them just might save future harvests.

Both scientists are National Association for Plant Breeding (NAPB) Borlaug Scholars — named for Nobel Peace Prize winner Norman Borlaug, who helped spark the Green Revolution. The scholarship pairs young researchers with mentors to sharpen their skills and broaden their vision.

For Singh, it’s been a crash course in communication.

Jeffery, in turn, is rediscovering her own strengths through mentoring.

In a world racing to adapt to climate change, shifting diets, and population growth, the work these two scientists are doing is important. Deep in the genome, at the intersection of tradition and technology, they are planting something more durable than any single variety — a roadmap to the future of plant breeding.