Canada’s seed industry needs an intellectual property wake-up call, Seeds Canada conference hears during closing session.

To close out today’s Seeds Canada Annual Conference in Quebec City, three of North America’s top seed industry leaders — Carl Potts of Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, Eloy Corona of the U.S.-based Seed Innovation and Protection Alliance (SIPA), and Ellen Sparry of C&M Seeds — sat down for a frank panel discussion on the future of intellectual property (IP) in seed breeding.

Moderated by Bryan Gerard of JoMar Seeds, the session made clear what’s at stake: if Canada wants a competitive and sustainable agriculture sector, it must get serious about protecting plant breeders’ rights. And if the country fails to act, industry leaders warned, it risks losing the very innovation that underpins its agricultural success.

Killing the System That Feeds Us

“There’s $870 million in value left on the table in the U.S. every year due to seed piracy,” said Eloy Corona, who leads SIPA, a U.S.-based group focused on IP protection and education. “This isn’t just a legal problem — it’s a structural challenge for innovation.”

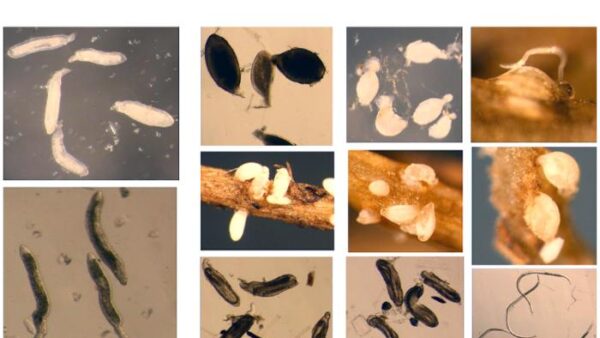

Corona described a three-pronged approach: protection, prevention, and enforcement. SIPA, he explained, works not only with seed companies but also with universities, auditors, IP law firms, and even diagnostic labs to build a coordinated front. Recent efforts have included anonymous tip lines, digital outreach campaigns, and grower audit programs aimed at detecting unauthorized seed saving.

“In many ways, we’re trying to create a culture of compliance,” he said. “It’s about changing behaviour — not punishing people, but showing them the value of doing things right.”

Corona shared anecdotes ranging from U.S. soybeans to Italian tomatoes — where enforcement once had to involve state police due to criminal involvement in seed piracy. In every crop, he said, the story is the same: “Innovation costs money. If we don’t protect it, we kill the very system that feeds us.”

Canada’s Shifting Landscape

Potts brought the conversation home to Western Canada. As executive director of Saskatchewan Pulse Growers (SPG), he represents over 15,000 producers of crops like lentils, peas, and chickpeas — staples in both domestic and global food systems.

Canada has long led the world in pulse production, Potts said, but that lead is under threat. “Russia is taking over our traditional markets for yellow peas, and Australia is making gains in red lentils. We can’t afford to stand still.”

SPG is moving forward with a bold new model that ties breeding investment to royalty returns — on both certified seed and farm-saved seed. It’s a shift that hasn’t come easily.

“Some growers are used to saving seed from one year to the next,” Potts acknowledged. “But if we want better varieties — disease resistance, herbicide tolerance, improved quality — we need to create an environment where breeders get rewarded for success.”

To that end, SPG has launched agreements with Limagrain and J4 Agri-Science, and is in discussions with the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre to implement similar IP frameworks.

The key, Potts said, is farmer buy-in. “The farmers around our board table see the need for long-term investment. And when we ask growers what they’d pay for varieties that can withstand diseases like root rot, the answer is often ‘anything,’ because without it, they’re out of business.”

“They Want to Pay for Value — But Show Them the Value”

Sparry’s voice added both historical weight and a note of exasperation. As head of Ontario’s C&M Seeds, she’s been advocating for strong IP protections since the 1990s.

“I’ve been telling this story since ’96,” she said, referring to her long-running efforts to protect breeder-developed wheat varieties in Ontario and beyond. “We’ve always believed in doing this right. But how do we tell that story differently so that growers really hear it?”

Sperry emphasized that IP isn’t just about paperwork. It’s about trust — between breeders, seed companies, and the farmers they serve. Her company works with a slew of breeding programs globally and makes it clear to every partner that IP protection is non-negotiable.

Still, adoption varies wildly across Canada. In Quebec, where crop insurance is tied to certified seed use, uptake is as high as 90%. But in Ontario, it hovers closer to 60%. And in Western Canada, adoption of certified seed in wheat and pulses often lags far behind.

Giro put it bluntly: “We need to stop talking about acres and start talking about dollars. What’s the value of those 80% of acres that aren’t using certified seed?”

Enforcement Remains the Missing Piece

The conversation shifted to enforcement — and the roadblocks Canadian companies face in court.

An audience question: without clear legal precedents for damages, how can companies justify the cost and time it takes to enforce their rights?

Corona responded by describing U.S. approaches, where companies sometimes include pre-calculated damage clauses in grower contracts. He cited past examples from Monsanto where multipliers — based on how many acres a single seed acre could generate — were used to calculate settlements. “The courts didn’t love it,” he admitted. “But it gave us a framework.”

He also pointed to Latin American countries like Colombia, where fines for infringement are tied to average monthly salaries — a different but equally forceful approach.

The panel agreed: enforcement in Canada is inconsistent and underdeveloped. Without stronger legal mechanisms or government-backed deterrents, companies are left to police the system themselves.

A Culture Shift in Progress

Still, there were signs of optimism. Potts noted that in the latest round of outreach to farmers, declaration rates on farm-saved seed had increased fourfold. “That shows people are responding,” he said. “We just need to keep the momentum.”

Corona added that the next generation of plant breeders is eager to innovate — but only if they believe their work will be protected. “The young breeders coming out of university are phenomenal,” he said. “They’re working with gene editing, CRISPR, new breeding techniques. But to justify the investment, they need to know their innovations will be respected.”

In the end, the conversation returned to the farmer. “Growers want value,” said Sparry. “If we can deliver that — disease resistance, better yields, better markets — they’ll come along. But we have to bring them with us.”