The impact won’t show up tomorrow, but five to 10 years from now, farmers may feel it in lost yield gains, weaker disease packages, and a slower pipeline for new varieties.

While innovation in agriculture is often associated with new equipment and digital tools, a fireside chat hosted by Alberta Seed Guide editor Marc Zienkiewicz at the CrossRoads Crop Conference in Edmonton, Alta., on Jan. 27 argued the most important technology on most farms is still seed — especially in light of the recent news surrounding layoffs and closures at Agriculture and Agro-Food Canada (AAFC).

“Innovation doesn’t always look like a new gadget,” said Zienkiewicz. “For most farmers, the most innovative technological product that you have on the farm every year is still seed. It’s your most fundamental input.”

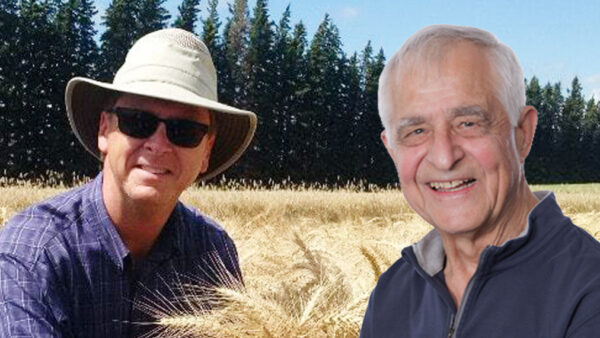

The discussion featured Doug Miller, executive director of the Canadian Seed Growers’ Association (CSGA), and Kenny Piecharka, country manager for KWS Seeds Canada in Lethbridge. The panel focused on what’s already working on farms today — from genetics to seed certification — and what farmers should be watching as Canada’s public research capacity faces uncertainty.

Seed certification as a “trust layer”

Miller described CSGA as Canada’s national seed crop certification authority, with a 120-year history. He said its work centres on delivering one national certification program and setting standards across about 70 crop kinds.

“Seed certification, in essence, is really a trust layer,” Miller said, noting it helps farmers make confident decisions by ensuring transparent standards around quality and identity.

He also highlighted ongoing modernization efforts, including the potential for digital tags on certified seed. Instead of relying on handwritten or dot-matrix printed tags, he said the future could include QR codes that link farmers to key information such as variety details and certificates of analysis.

“As a sector, we can’t be relying on a dot matrix printer to be able to drive our sector forward,” Miller said.

Hybrid rye and faster breeding cycles

Piecharka outlined KWS as a 170-year-old German family-owned breeding company working in 11 of 13 major field crops, plus vegetables.

He said KWS’s hybrid fall rye has become a major success in Canada. Testing began in 2012, with commercial availability starting in 2014, and KWS Seeds Canada launched in 2022.

“Canada is a rye country,” Piecharka said, noting the crop once exceeded three million acres. KWS now produces hybrid rye seed in southern Alberta and sells it across Canada.

Piecharka said plant breeding innovation has accelerated through speed breeding enabled by greenhouse advances.

“Innovation has got faster due to technological advancements and speed breeding,” he said, adding that modern breeding programs increasingly require pathologists, genotyping and phenotyping to respond quickly to shifting disease pressures.

AAFC research cuts raise long-term questions

The conversation shifted to recent news about reported AAFC research station closures, including Lacombe, and potential job reductions over the coming years.

Zienkiewicz noted farmers won’t feel the impact immediately.

“The varieties that you rely on are still there,” he said. “The pipeline is not going to dry up overnight.”

But both panelists warned the real consequences may emerge five to 10 years from now, when the sector starts asking where the next yield gains or disease resistance packages went.

“With the closing of these stations, we’re losing valuable capacity in terms of infrastructure, in terms of personnel, in terms of germplasm,” Miller said. “That’s not something we’re going to get back.”

Piecharka pushed back on the idea that private breeding can quickly replace public breeding capacity.

“There’s no easy button approach to this,” he said. Entering a market like Canadian wheat, he added, can require “five to 10 years minimum of investment,” including adaptation work and infrastructure, and depends on confidence that investment can be recovered.

Adoption and collaboration

Miller also raised the issue of productivity, pointing to early research suggesting farmers may be leaving significant value on the table by sticking with older genetics.

“How many are still relying on genetics that are 10-plus years old?” he asked.

He argued certified seed plays a role not only in on-farm performance but also in funding the next generation of innovation.

“When you buy certified seed, you’re really investing in that next generation of research,” Miller said.

Piecharka emphasized that innovation requires collaboration across the entire seed value chain.

“It takes a village to bring a new product to market and to get seed in the farmer’s hand,” he said. “We really need dialogue. We need feedback to understand what challenges you do have on the farm.”

In closing, Miller urged farmers to stay engaged as the seed system evolves.

“You have a stake in what happens next,” he said. “Make sure that you’re around that table.”