As farmers nail down their winter wheat seed purchase, they’ll also need to determine if and what seed treatment should be included.

Cereals are a very diverse crop and the management options recommended for pest control are just as diverse. They are dependent upon the geography, needs of the farmer and key diseases. Inthat regard, pest controlis quite differentfrom soybeans or even corn. When helping farmers prepare and planpest controlfor their winterwheatcrop, it’s important to get an accurate picture of the disease and insect pressure. Always keep geography top of mind.

“If you’re inthe Southern United States, disease and insect pressure will be differentfrom the Pacific Northwest,” says Josh Kelley, Syngenta Cereals and Diverse Field Crops product lead in North America. If you’re ina NorthernPlainsenvironment, wireworms are going to be a key pest. You willalso have soil- and seed-borne Fusarium.”

From an insect standpoint, there can be very differentinsect spectrums, as well. Whether it is wireworms or aphids, they can all limit yield potential and restrict root health, predominantly inthe case of barley yellow dwarfvirus(BYDV). Insects create openings intothe plant, which make it susceptible to diseasesand viruses that affectoverallyield.

Geography really dictates what seed treatments should be applied on the seed.

InTexas, Oklahomaand New Mexicointhe SouthernPlainsgeography where it is much drier, you willsee more Rhizoctonia and more Fusarium with more aphid pressure and more Hessian fly.

Hessian fly is also a problem in southern climates. To help suppress Hessian fly, increase the rates of neonicotinoidsinyour seed treatment. “With Cruiser, we promote maximum label rates,” states Kelley. Hessian fly is more dominant inthe Southeastern United StatesinArkansas, Mississippiand Alabama, and then overto the Carolinas on the East Coast. We see this pest from time to time inother areas, but Hessian fly is predominantlya problem for the SouthernU.S. geography.

“As you move intothe NorthernPlains, or even intothe Pacific Northwest, wireworms are a huge issue — there are six speciesthat are of economic importance,” Kelley says. “Old prairie ground really favors wireworm specieswhere you can have significant yield losses of 50 percentto sometimes as much as 80 percent.

“Products such as Cruiser (thiamethoxam), imidacloprid and clothianidin provide some protection on wireworms.”

Aphid Invasion

“Aphids, depending on geography, can be an issue every year, or they may be an issue once every several years,” Kelley says. “The biggest challenge with aphids is that they transmit BYDV.”

The five speciesof aphids that can transmit BYDV are bird cherry-oat aphid, corn leaf aphid, English grainaphid, greenbug and rose-grass aphid.

Kelley explains that wheatinfested with BYDV willhave undeveloped root systems. The disease decreases tillering and may also cause some delayed maturity.

It’s not a problem every year, Kelley says, but by using strong chemistry on the seed, seed treatments willprovide a level of insurance regardless of the environment.He shares that an applicationof Warrior II with Zeon Technology (Lambda-cyhalothrin)insecticide inthe springwillcontrolall types of aphids and impedes the spread of BYDV.

Three Detrimental Diseases

The key diseasesincereal crops, and specifically winterwheat, are Fusarium, Rhizoctonia and Pythium. Three elements are needed to have disease pressure ina field: a host, the pathogen and an environment. Obviously, there are many other bunts and smuts that may occurindifferentgeographies.

Pythium is a killerand likes cool, wet conditions. It willkill crops. It’s a huge disease incereals and is also incorn and soybeans. Pythium is a problem inareas where growers are pushing the envelopeto get their crops planted, when the soil temperature is not quite ideal.

“We had a wet springinsome areas in2018,” Kelley says. “Growers were really putting their seeds invery moist, saturated ground, and we heard of Pythium issues popping up.”

On the flip side, Rhizoctonia favors a warmer, drier environmentbut won’t kill crops, such as Pythium. In 2018, Kelley saw instances of huge Rhizoctoniapressure early inthe season. The crop survived but at harvest the disease made a significant impact.

Fusarium also favors dry conditions and attacks the plants’ root hairs.

“You don’t know inadvance what the planting season willbring,” says Kelley. “You may have warm, dry weather or you may have a cool planting season. A seed treatment willprovide protection, regardless of what the environmentthrows at you.”

Research and Response

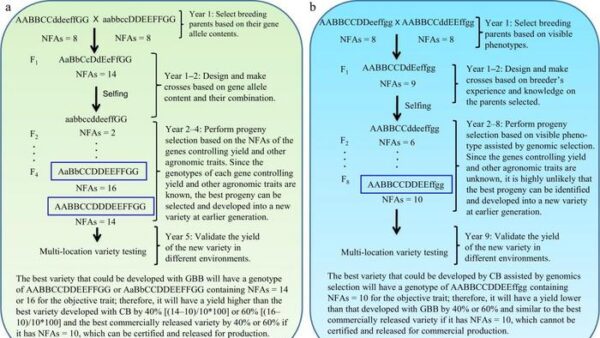

North Dakota State University researchers have accumulated 14 years of seed treatment data dating back to 2003 for hard red spring wheat (HRSW) stand and yield response to fungicide seed treatments. These trials are primarily conducted near Fargo, which is located near the North Dakota-Minnesota border, and Dickinson, which is nearly 300 miles west of Fargo and within 60 miles of the North Dakota-Montana border. These two seed treatment trial locations are in very different types of production systems with very different yield environments.

Of the 41 experiments represented by the data set, 135 treatments were conducted in the Fargo region with a non-treated check mean yield of 69.6 bushels per acre. Across all trials in the western region near Dickinson, 75 treatments had a non-treated check mean yield of 36.1 bushels per acre.

“Production in the western half of North Dakota is predominantly no-till with small grains being a focal point in production,” says Andrew Friskop, North Dakota State University Extension cereal crop pathologist. “Western trials are all conducted in growers’ fields. Whereas, production in the eastern half of the state, including Fargo, is predominantly conventional till. More than 95 percent of the eastern North Dakota trials have been challenged with Fusarium or Cochliobolus.”

Since 2013, Friskop has overseen these trials.

“The primary use of fungicide seed treatments in North Dakota is to control both seed-borne and soil-borne diseases,” he says. “The one seed-borne disease that we most commonly encounter is loose smut in our small grains.”

Loose smut is found in spring wheat, winter wheat and spring durum wheat. To a lesser extent, Friskop finds some common bunt. He says due to growers’ widespread use of fungicide seed treatments and certified seed, there are generally few issues with seed-borne diseases causing yield reductions in North Dakota.

The other way that seed treatments are used is to suppress soil-borne root rots.

“When we think of root rots in North Dakota, there are several ways they can attack the plant. For example, with Fusarium, we can have some crown rot issues,” Friskop says. “We can also have some sloughing-off of roots, or we can have some lesions that start early and girdle the stem throughout the season.”

Regardless, there is no shortage of root rots or seed decay that can potentially occur in North Dakota. In the past five years, he says the three diseases that seem to pop up most frequently are Fusarium crown rot, common root rot and Pythium root rot. Although some of these diseases prefer different environments and different conditions, they often occur in a complex.

Because of that, when thinking of seed treatments from a fungicide perspective, one of the first words that come to Friskop’s mind is broad-spectrum.

“When it comes to the importance of fungicide selection, it depends on the disease.”

Trial Responses – Interpreting the Data

Since Friskop started in 2013, he has conducted several seed treatment trials and created a huge data set to give a summary of the results. This data encompasses 41 experiments with more than 210 replicated treatments.

“For the replicated treatment, think of it as a fungicide or a combination of fungicides’ effects on the improvement of stand and yield,” Friskop says. “We have done several studies, and we know what type of active ingredients can be effective on the specific pathogens that we’re studying, but more importantly, what type of active ingredients can be effective across an entire field.

Friskop notes that it’s difficult in trials to correlate a seed treatment with yield.

“A seed treatment’s biggest effect occurs early in the growing season,” he says. “There’s a lot that can happen between the time the trial is put in the ground to when the crop is harvested.

“When you think of small plot research, if you see some early season stand reduction, wheat plants have a great ability to compensate by tillering more. Often, you won’t see a strong correlation between stand and yield. The general trend that we’ve been seeing across these areas is a positive response in both stand and yield when a seed treatment was used.”

In the eastern trials, Friskop says there was a 4.9 percent increase in stand when a fungicide was used. In the western experiments, there was a 9.4 percent stand increase. About 60 percent of the eastern trials had a positive yield response while in the western trials, there was a positive response about 75 percent of the time when fungicide seed treatment was applied.

Looking at those same data sets, Friskop shares the mean yield response in the eastern trials was 2.2 percent higher for the fungicide seed treatment plots and about 4.5 percent higher for the fungicide seed treated plots in the west. In both locations, a positive yield response was observed more than 70 percent of the time when a fungicide was applied.

“The one thing I must add though, is that any time you look at yield data, remember that even though a positive yield response was observed 70 percent of the time, it does not always mean it was an economic yield response,” adds Friskop.

Looking at yield responses, Friskop says both locations averaged about 1.5 bushels per acre yield increase from the use of a fungicide seed treatment.