How does agriculture affect different endangered species in the U.S.? How are seed companies trying to help? Experts explain.

Crops, vegetables or flowers growing are a beautiful sight. However, we often don’t think about the animals, plants, fish, birds and invertebrate species that may be impacted by human exploits, including agriculture. The facts show that there is room for improvement for the agriculture industry to be better stewards of the land. We share the Earth with many species — and it is up to us to protect those species and make sure that our efforts don’t damage the land or other species’ habitats.

Impact of the Endangered Species Act

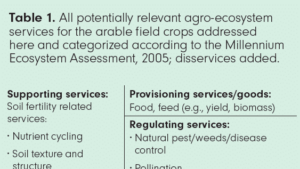

Since its passage in 1973, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) has impacted how farmers are allowed to use certain products. The U.S. Department of the Interior and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) enforce the ESA, while the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approves all insecticides, fungicides and seed treatments before they go to market.

“It’s very difficult from a science and legal administrative viewpoint because all species have to be taken into consideration during product review, which may or may not be an issue for some locations,” says Laura Peterson, head of federal government & industry relations with Syngenta. “Because seeds and/or crop protection products may be used in any given county, there is a lot of uncertainty to account for.”

Becoming an Endangered Species

According to the USFWS, species that are protected by the ESA fall into either one of two categories — threatened or endangered, depending on its status and the degree of threats that the species faces.

An endangered species is defined as one that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range. A threatened species is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future.

To help conserve genetic diversity, the ESA defines species broadly to include subspecies and distinct populations of vertebrates.

A species is added to the endangered species list when it is determined to be endangered or threatened due any factor, including the present or threatened destruction, modification or curtailment of its habitat or range; overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific or educational purposes; disease or predation; inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; and/or other natural or manmade factors affecting its survival.

A strict legal process called a rulemaking procedure is followed by federal agencies to propose and adopt regulations. The first step in assessing a species’ status is the publishing of notices of review by the USFWS to identify species they believe meet the definitions of threatened or endangered in the Federal Register, a daily Federal Government publication. The next step is seeking biological information that will help complete the status reviews for candidate species.

The USFWS has a priority system to direct their efforts toward the species with the greatest need. The priority system sorts species by the degree or magnitude of the threat, followed by the immediacy of the threat and the taxonomic distinctiveness of the species. Popular species or so-called “higher life forms” do not get special preference from the ESA.

Once proposed species are listed in the Federal Register, any interested person can comment and provide additional information on the proposal during a 60-day comment period and submit statements at any public hearings. The USFWS also promotes awareness of proposals through news releases, special mailings and by informing the scientific community. Public hearings are held in cases of high public interest or if an interested party asks the USFWS to do so within 45 days of the proposal.

All information received in public comments and testimony is analyzed during final rulemaking. A final listing rule generally goes into effect 30 days after publication in the Federal Register.

Once a species is officially added to the Endangered Species List, protective measures apply, such as protection from adverse effects of federal activities; restrictions on taking, transporting, or selling a species; authority for the USFWS to develop and carry out recovery plans; authority to purchase important habitat; and federal aid to state wildlife agencies that have cooperative agreements with the USFWS.

Rusty Patched Bumble Bee

An endangered species that is certainly of interest to farmers is the rusty patched bumble bee (RPBB), which calls the grasslands and tallgrass prairies of the Upper Midwest and Northeast home. At one time, its range included 28 states. Since 2000, the RPBB has been reported only from 13 states and Ontario.

According to information from the USFWS, the bees’ habitat has been converted to farmland or developed, so remaining grassland areas tend to be small and isolated. The RPBB can also absorb toxins directly through their exoskeleton through contaminated nectar and pollen.

Climate change may also play a factor in harming the RPBB, such as increased temperature and precipitation extremes, increased drought, early snow melt and late frost events. These events may lead to more exposure to or susceptibility to disease, fewer flowering plants, fewer places for queens to hibernate and nest, less time for foraging due to high temperatures, and asynchronous flowering plant and bumble bee spring emergence.

The RPBB’s endangered status has not caused any limitations on farming and sightings of the RPBB have increased.

Butterflies

While not historically valued for pollinating agricultural crops like bee species, there are a lot of butterflies on the endangered species list. One example is the Karner blue butterfly. The Karner blue butterfly is very dependent on blue lupine, as blue lupine is where the butterfly lays its eggs.

So far, the Karner blue butterfly’s endangered species identification has not resulted in any limitations on farming.

Rebounding Species

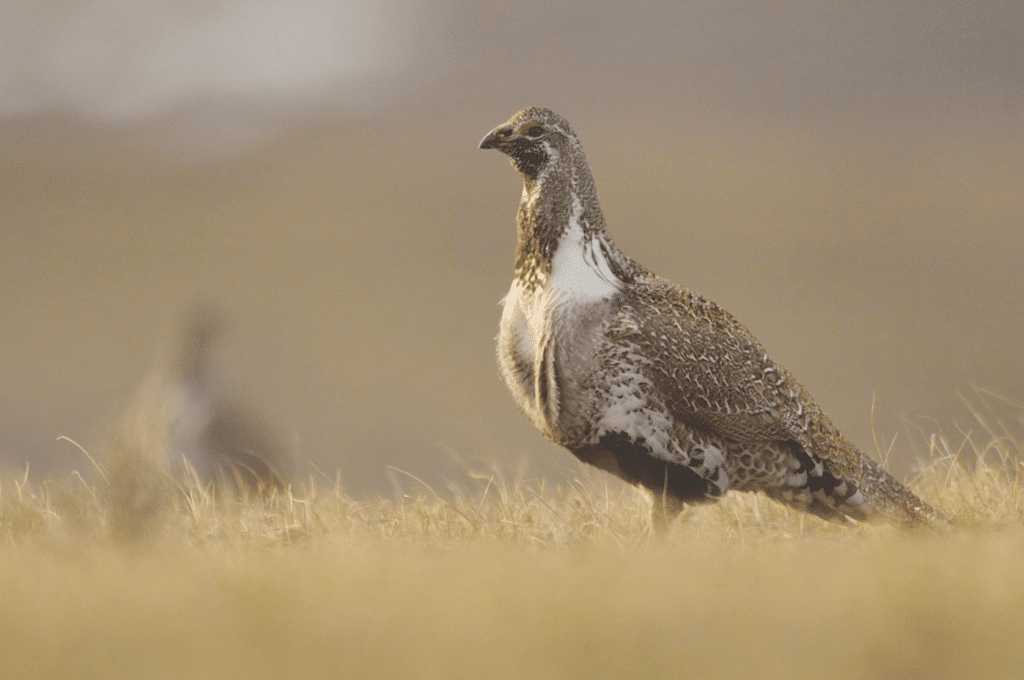

The seed industry has been very invested in working with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to help develop and maintain habitat for the near threatened sage grouse. Out of the 250 million acres owned and maintained by the BLM, about 2 million of those acres are sage grouse habitat.

“The sage grouse was a prime example of a real-life situation where a species was very close to being listed, but between government agencies, ranching and other motivations, there was common alignment to keep that species off the endangered list,” says Rob Wendell, CEO of Granite Seed.

To help increase habitat, in the past three years alone, the native seed industry has supplied more than 500,000 pounds of sagebrush seed. Wendell notes that many of his seed industry colleagues have done the same in the past five to seven years.

Another example of governmental agencies working with farmers to protect a species is the Working Lands for Wildlife program from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). New England farmers were able to help the New England cottontail when it was being considered for listing as an endangered species.

Establishing Habitat & Promoting Biodiversity

It’s not something you often hear much about, but ecological biodiversity impacts our environment more than we even know.

“When a species goes to extinct, it doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” says Diane Wilson, Trial Supervisor with Applewood Seed. “If diversity keeps plummeting in general, it is going to impact our crops and wildland plants, because there may not be enough pollinators or the right species of pollinators available for pollination. It will also affect all the wildlife that depend on native plants for food, habitat and protection, and impacts will be felt all the way up the food chain.”

Protecting wild pollinators is essential to maintaining our food supply, particularly as the global population swells and the demand for food continues to increase.

Bayer has been proactively working to help growers understand that land can still be productive and while hosting habitat.

“We’re not asking growers to put habitat in the middle of a corn field,” says says Aimee Hood, Regulatory Science Communications Lead with Bayer. “Farmers can be very clever with non-productive parts of their land by making those areas habitat.”

For grazing lands, farmers should ensure they are using best land management practices for native grasses.

“There are so many things that can be done, but there is only so much funding for any given conservation practice,” says Peterson. “Seed companies are committed to doing what we can to provide cutting edge tools to farmers and protect the environment so we can achieve both multiple objectives at once.”

Seed companies are also helping the ESA in reviewing products through the massive amount of data that they are able to generate, according to Peterson.

“The better data you have, the better decision you can make. You have to take the emotion out of the debate — what is more precious than our ecology and environment?” Peterson says. “When it comes to science, there is always room for improvement; it’s not all or nothing. It’s about making progress where possible.”

A way to help threatened species includes rejuvenating areas affected by wildfires where there may not be human population, but is still important habitat.

“We want to help prevent watershed and rehabilitate and prevent fire damage in the West,” Wendell says. “From a business and stewardship standpoint, everyone cares about promoting habitat.”

“Farmers just need to be given the tools to make it work,” she says. “They need to know how to prepare the ground, what plants to plant, how to manage a habitat plot, when insecticides can be applied and what type.”

Wilson adds that if producers want to help a specific endangered species, they just need to do a little research to find out what plants to utilize.

What Harms Species?

At times, consumers have not always perceived growers as being stewards of the land. However, many growers will establish habitat as one way to help consumers see the direct impact farmers have on their local community.

Other farmers are actively involved in conservation programs such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP).

“Most growers are good stewards, but it’s very important that the seed industry helps people understand how to be good stewards of their products,” says Hood.

Hood cites the industry initiative GrowingMatters.org as a great resource to help farmers understand how to responsibly use treated seed and pesticides while protecting habitat and ensuring minimal impact.

Overcoming Obstacles

There are always going to be growers who resist implementing these tactics. For those who may be hesitant, Hood suggests just trying it.

“I’ve seen farmers successfully establish habitat and become addicted to it, because they see the advantages it offers them,” Hood says. “It will be a little work in the beginning, but for example, in a cost-share program, they are getting money back on non-productive land.”

Hood shares an example of an Iowa farmer who established habitat that also helps his soil quality, prevents runoff and improves air quality around his farm while also bringing animals back to the property to preserve biodiversity.

“Just giving it a try is a start in finding out there are real benefits. Finding the balance between growing crops and implementing conservation practices will be advantageous in the long-term,” Hood says.

Seed companies do recognize that there is a cost involved with conservation efforts, Peterson adds.

“We support our farmers, listen and seek to find understanding. The cost concern is absolutely a factor,” she says. “With our global perspective, if we had a five to 10% increase in conservation, that would be a lot of acres. Although we understand the costs, we still want to help farmers be profitable.”

Another obstacle can simply be the time needed to build the infrastructure to better facilitate habitat establishment. For example, wild plant species that provide sage grouse habitat can only be collected during short windows in the fall, under harsh environmental conditions. It can take three to five years for companies like Granite Seed to figure out how to grow those wild plant species to scale and of high enough seed quality and efficacy so it will grow in different environments.

“Our job is to rally around the direction we’re given to provide the material, but it’s a big investment,” Wendell says. “It’s not easy to do, but that’s our commitment and sacrifice around protecting habitat that needs to be protected.”