Technology can help breeders keep pace with science.

Not to belabor a worn out joke, but … Plant breeding? Yes, there’s an app for that.

In fact there are several, and they’ve become a key part of the breeding and selection process for breeders around the world. New technologies in plant breeding bring with them mountains of data that simply cannot be processed and analyzed effectively with older methods.

Instead of continuing on with pencils, paper and possible spreadsheets, breeders are taking advantage of the ability of mobile devices to not only save time and store vast amounts of data, but also to cut down on the types of mistakes that could be common with older methods.

“If you’re using pencil and paper, if you’re using Excel sheets, it’s just going to slow you down,” says Dieter Mulitze, president and chief executive officer of Agronomix Software, Inc., based in Winnipeg, Canada. “Breeders are realizing the limitations of that.”

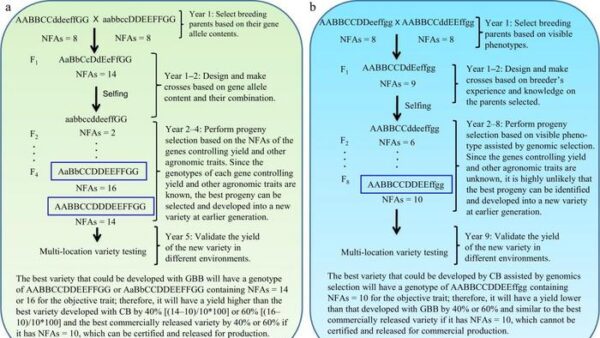

A significant part of the digital revolution in plant breeding comes from the advent of genomic tools that make it easier for breeders to see details, down to changes in single alleles or a variation of a single gene.

“Parts of DNA will change by one allele or a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). To map that, you’ve got to sequence it,” Mulitze says. “There are new bioinformatic methods being developed all the time.”

And to keep up, software creators are constantly adding to the breeder’s toolbox to ensure that the mountains of data that are recorded can be stored, analyzed and used to make the best decisions in the lab and in the field.

Mistakes Will Be Made

To be clear, the average Microsoft Excel user likely has no concept of how powerful a spreadsheet tool they have in that program. Data can be sorted, arranged, compiled and analyzed through the more technical functions of the program.

But for a plant breeder, the process of getting the information to those sheets in the first place is fraught with problems.

Some breeders will log observations in a notebook with pen or pencil and then sit down at a computer at a later time to transcribe that data into the spreadsheets. It opens the breeder to the possibility that a fat finger could turn a five into a six or that weary eyes could skip a line or two and throw off the observations.

Others might have a tablet or laptop on site and record the data to the sheets in the field. But even that can be a time-consuming process since Excel isn’t designed for in-field data recording.

On top of that, those using spreadsheets will find that long-term observations will require multiple tabs and sheets, spreading the data out and making comparisons and analysis difficult.

And if the breeder wants to take photos to go with the observations, that all has to be kept organized so that the photos can be downloaded from a device and later matched with the data recorded. With mobile, web-based devices, the photos taken in the field can be automatically paired with the data.

“You have a myriad of files that are very hard to audit and hard to reconcile if you want to analyze data. As a breeder, you can spend hours, if not days, reconciling data before an analysis,” shares Oskar Laufer, vice president of sales and business development for the Israel-based Phenome Networks Ltd. “You would be surprised what companies are still using Excel spreadsheets to manage their data.”

The more sophisticated web-based systems allow those phenotyping the plants to make record observations in the field using a mobile device whether there is an Internet signal or not. Later, when the device connects to the web, the data recorded that day is uploaded into a database.

Breeders could also run into problems if they are part of a collaboration or a company that is phenotyping plants in multiple locations. If they’re using a system that uses spreadsheets or is not web-based, all the data collected from those sites will have to be sorted and combined — a painstaking process.

“Each breeder has his own way of working, more or less,” says Ineke Leidelmeijer, a commercial consultant for Netherlands-based Agro Business Solutions B.V. “You can do your own tests and record your own data in your own way. If you have to compare it with another breeder, it can be a challenge.

“When you’re the only breeder, this is OK, but when you’re working with multiple breeders, having one system is essential.”

As companies become more global in nature and test hybrids at multiple sites around the world, that becomes more of an issue.

“If the breeder is looking for wide adaptation, data is collected from numerous locations. That’s really important,” Mulitze says.

Laufer adds that even in the same company, breeders in different locations may simply see things differently without a standardized program guiding them along the same path.

“The more spreadsheets you get, the more difficult it is to keep things the same across the company,” Laufer says. “One breeder may define fruit firmness in a different way than another or measure a trait with a different scale.”

Keep It Simple

One of the key features of many of the breeder programs out there is a program’s ease of use in the field. Breeders could make tens of thousands of observations per day, and their productivity can be tied directly to how long it takes them to do repetitive tasks such as typing in data.

Mulitze says his company looks for ways to reduce the number of keystrokes that have to be made in the field. One feature allows users to enter data and forces the cursor into the next data entry point automatically.

“If you make 10,000 observations in a day, you could have to press ‘enter’ 10,000 times, and that’s a waste of time,” Mulitze says.

Barcodes and scanners not only save time, but ensure that the data is input in the correct place.

And once data is entered, it needs to be accessible. Search functions with many of the software programs out there make pulling up data and comparing it side by side much easier than wrestling with columns of data from multiple spreadsheets.

“The real challenge is to find the data, make it comparable and access it,” Leidelmeijer says. “Then you need to interchange it with other field inspections and other observers.”

“[Breeders] need to be able to take all that genetic data and relate it to the phenotypic data available.”

— Dieter Mulitze, Agronomix Software, Inc.

Climbing the Mountain

There was a time when breeders observed their lines, chose plants with desired features and made their crosses. They kept the best of those hybrids and started again.

That system alone created a significant amount of data that would have to be sorted and analyzed.

“It’s a lot of data, crossing parents, results of the offspring they create, field observations they do,” Leidelmeijer says.

Today, the eye test and intuition certainly still play a role. But the unlocking of genetic codes has supplied breeders with more data than they once could have imagined.

Not only are breeders selecting for particular genes, they can drill down to SNPs — single nucleotide polymorphisms — the difference in a single A, G, C or T in a plant’s DNA. Those differences are alleles, and they allow breeders to significantly increase the pace and precision with which they create crosses.

“The amount of data has increased dramatically with the introduction of genetic markers and the industry becoming more global,” Laufer says.

“This is something that’s becoming more and more important for breeders,” Laufer adds. “Not all the breeders we talk with are working with genetic markers, but they all say they will be one day.”

The Possibilities

The selling point for the major companies pushing software technology designed for breeders is in the analysis. At the end of the day, all that data has to mean something.

Once physical traits are recorded, breeders can upload genetic analyses of those plants to determine which genes may be responsible for the plant’s characteristics. That’s not something likely to be done in a spreadsheet or with pencil and paper.

“They need to be able to take all that genetic data and relate it to the phenotypic data available,” Mulitze says.

It could be that the genes responsible for a particular trait aren’t known. The programs can identify genetic sequences that could be at play, allowing breeders to make new discoveries.

“We don’t have markers for everything,” Mulitze says. “We don’t have them all identified.”

The databased information can also be recalled for long periods or specific conditions, allowing breeders to understand how their lines react to different climates, for instance. “We can pull out all the data for a trait. Here’s a couple of plants, pull the data for the past five to 10 years for wet years or dry years,” Mulitze says.

Laufer says there are also crossing recommendation tools under development that will give breeders a glimpse of the likelihood of success of a cross between two parent plants, based on an advanced algorithm and machine learning, and will help breeders to make better decisions.

If there are 1,000 parent lines available, there are hundreds of thousands of potential crosses available to make. Breeders can use a prediction tool not to replace their skill, but to see possibilities that might have been otherwise buried in that mountain of data.

“You can follow your gut feeling, or go on some analysis you have, but the possibility that you have a successful cross is small as it is,” Laufer says. “It’s not supposed to replace the decisions by breeders, but it will help breeders mine the data breeders gathered and make recommendations.”

What software companies really want to get through to breeders is that there is a world of technology out there that can vastly improve their abilities to record, store, sort and analyze the data they need to create successful hybrids. And using that technology keeps those breeders doing what they do best rather than fiddling with programs that were never designed to do the job in the first place.

That technology is also changing as the science involved in breeding changes. When molecular markers became a significant method of identifying the genes responsible for plant characteristics, the software companies were able to incorporate that into their technologies.

“Plant breeding data management and plant breeding software has made huge steps in the past 10 years,” Laufer says.