In a letter to Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack, the U.S.-based Independent Professional Seed Association calls the country’s current business environment a threat to American competitiveness.

The U.S.-based Independent Professional Seed Association (IPSA) is calling for an overhaul of the country’s intellectual property (IP) laws, branding the current IP framework as a threat to American competitiveness in seed and beyond.

That’s according to IPSA CEO Todd Martin, who recently penned a letter to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack on behalf of IPSA members in response to the USDA’s request for comment on the intellectual property system as it regards seed and other agricultural inputs.

The request for comment is related to President Joe Biden’s 2021 executive order seeking to address what it calls the trend of corporate consolidation throughout the economy.

“American agriculture has enjoyed a century of innovation. Innovative plant breeding brought forth corn hybridization. We have seen additional productive measures brought forth in synthetic fertilizers, pest control systems and mechanization. But there has been no parallel to the consolidation of the agriculture industry since the biotechnology revolution during the 1990s,” IPSA says in the letter.

IPSA notes that in 1992, there were 12 major multinational companies involved in crop protection inputs for row crops, including seed. Today, that number is four. In that same period, the market has lost 100 independent seed companies in the United States.

“Not only did the corn and soybean seed market consolidate, but ownership also moved outside of the United States. With consolidation in the agriculture industry, our businesses remain under constant threat, as does American competitiveness,” IPSA goes on to say in the letter.

In an interview with Seed World, Martin says independent seed companies are being hit hard by a business environment that is getting harder to operate in, in part due to the IP framework that he says allows companies — to increasingly control a bigger portion of germplasm.

“We’re in a business environment where four companies control the major germplasm in cotton and corn and control all the vital technology in those crops, plus soybeans. It’s an extreme level of competition and an extreme level of concentration of competition,” Martin says.

In the letter, IPSA notes that four corporations account for 85% and 76% of corn and soybean seed markets. Furthermore, genetically modified seed prices rose more than 700% between 2000 and 2015.

“Even more concentrated is the ownership of corn elite germplasm. About 90% of the commercial varieties are owned — directly or indirectly through licensing — by two companies. Bayer Crop Science recently declared its germplasm ownership share at 55% and 35% can be attributed to Corteva — a concentration far higher than in any other country,” the letter notes.

Caught in the Middle

In the middle of all this are independent seed companies that license intellectual property in the form of traits and genetics from these suppliers, and also compete against these suppliers in the marketplace.

“Small businesses, which include independent seed companies, are real economic engines in communities. They create real jobs. They generate real economic benefits much more so than corporations do with their thousands of people employed. We’re talking about millions of people in the United States employed by small businesses,” Martin says. “This is not something we can lose.”

At the heart of IPSA’s concerns about intellectual property are the rules concerning patents in the United States.

“Innovation needs to be rewarded”, Martin says. “The current patent system rewards innovators for 20 years. The very reason patents expire is to allow others to improve on existing technology. A system that continues to hold innovations too closely and does not allow outside improvement must be changed.”

Martin notes that IPSA members are very concerned about adequate access to technology. While it is appropriate that registrant companies have their voices heard, including the right to communicate with EPA, their economic interests do not align with those of future trait registrants and farmers interested in purchasing post-patent, traited products, he says.

The first commercial biotechnology event in the United States went “off-patent” in 2014. However, no substantial post-patent use of biotechnology events has so far emerged, he notes.

IPSA would like to see two major overhauls made to the United States patent framework, namely:

- Patent laws must be shown to be reasonable and not perpetual. The ability to artificially extend patent life through legal manipulation must end, so that others may build new innovation on top of the current innovation, IPSA’s letter says.

- Further, IPSA proposes that current biotechnology traits have reached the point in the industry where there must be the freedom to access those traits by any company or organization without delay and under reasonable terms. Only by equalizing this biotechnology standard across the industry can we hope to see new genetic innovation and new development to propel us forward, the letter states.

“Innovation is at its best when people build on the work of others. Hybridization of corn came into this country in the 1920s. By 1940, it was 100% hybrid corn. Prior to that it was varietal. Where would we have been if the first company to commercialize hybrid corn had not allowed other people to build on top of that?” Martin says.

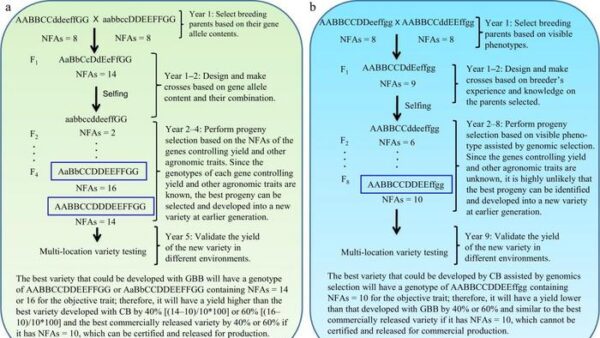

The letter to Vilsack notes that despite claims of continued genetic improvement resulting in greater yields, the current rate of genetic gain, as paced by the U.S. average corn yields, are very low at only 1.8% per year.

“If you look at average yields over the last 15 years, we have not seen that [genetic gain]. Granted, we have weather anomalies and everything else that come into play, but if we’re having genetic gain in field trials, that should start translating to genetic gain in terms of average yields.”

Despite issuing the letter to Vilsack, Martin acknowledges that it will be an uphill battle for IPSA to level the IP playing field in the United States. He says that out of 74 comments submitted to Vilsack as part of the USDA’s request, only a handful take a position similar to IPSA’s.

“We need other organizations to stand up and say, ‘Hey, we are looking at what’s happening in the marketplace and change is needed,’” he says.