Humanity’s demand for ammonia is immense — it’s a key ingredient in the fertilizers that power modern agriculture. For over a century, the go-to method for producing ammonia has been the Haber-Bosch process, which extracts nitrogen from the atmosphere and binds it with hydrogen. But while effective, this process is highly energy-intensive and relies heavily on methane gas, making it a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions.

Now, Professor Nikolay Kornienko from the University of Bonn has unveiled a more climate-friendly alternative that uses renewable energy to produce ammonia. His research team’s findings have been published in Nature Communications.

Fertilizers rich in nitrogen are essential to maximize yields of staple crops like grain, sugar beets, and potatoes — helping to ensure global food security. The Haber-Bosch process, developed by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch in the early 20th century, was a groundbreaking achievement that earned a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918. It works by using an iron catalyst under high temperatures (up to 500°C) and high pressure to bind nitrogen (from air) with hydrogen, forming ammonia, according to a press release.

Interestingly, nature has long outpaced humanity in this regard. Some plants, particularly legumes, form symbiotic relationships with soil bacteria that fix atmospheric nitrogen in a completely climate-neutral way — a process humans have yet to replicate on a meaningful scale.

The breakthrough from Kornienko’s team marks a step toward greener ammonia production, potentially transforming one of agriculture’s most carbon-intensive processes into a sustainable solution for the future.

“The Haber-Bosch process is extremely energy-intensive,” says Prof. Dr. Nikolay Kornienko from the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Bonn. Ammonia production is based predominantly on fossil fuels, which means that greenhouse gas emissions are correspondingly high. “In order to achieve the goal of a sustainable and climate-neutral society, the search for alternative ammonia synthesis processes is a priority,” says Kornienko, who is also a member of the transdisciplinary research area “Matter” at the University of Bonn.

Nitrogen Fertilizer from Sun and Wind

Alternative approaches to ammonia production have been under investigation for some time, with the goal of replacing the energy-intensive Haber-Bosch process. The vision: a system powered by renewable energy — sun and wind — where the required hydrogen is no longer derived from methane but produced by splitting water (H₂O) into hydrogen (H₂) and oxygen (O₂) using electricity.

It sounds straightforward, but the reality is far more complex. Scaling up ammonia production using solar and wind power involves navigating a series of chemical and technical challenges. The reaction pathways are delicate, and creating a stable, efficient process that can operate at industrial scale remains a significant hurdle.

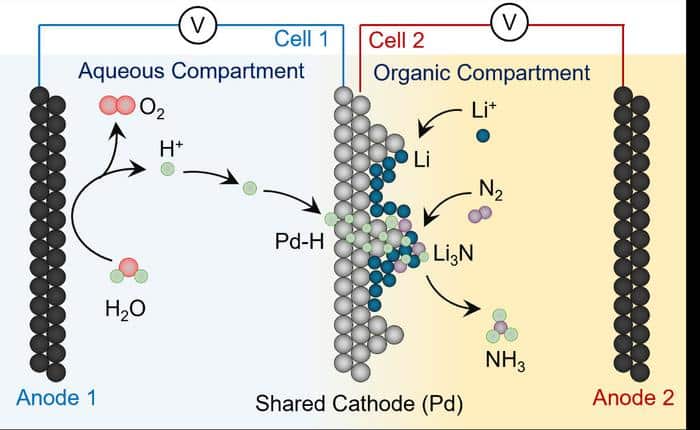

“The lithium-mediated nitrogen reduction reaction (LiNRR) is considered the most robust way to electrify ammonia synthesis,” says Hossein Bemana, the lead author of the study. In this system, lithium ions (Li+) are electrochemically reduced to a lithium metal layer. This lithium metal can then react with nitrogen gas (N2) to form a lithium-nitrogen compound. If a hydrogen source is available, the lithium-nitrogen compound is converted into ammonia (NH3) and dissolved lithium ions. Then the process starts all over again. That’s the theory, at least.

“We generally view this system as a model for the time being, as there are several practical difficulties,” says Kornienko. Because high voltage is required to reduce lithium ions to metallic lithium, energy efficiency is limited to around 25 percent. In addition, the system must operate in an air- and water-free environment, as lithium metal is highly reactive. Another challenge is that, similar to batteries, a porous solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) grows on the lithium layer. This layer must allow nitrogen gas and hydrogen to pass through as reactants to the lithium.

The Wrong Thing Is Sacrificed

Ideally, hydrogen would be sourced directly from water splitting. However, many current systems rely on alcohols as the hydrogen donor, and sometimes the solvent itself breaks down to provide hydrogen. “This makes the process impractical, as multiple alcohol or solvent molecules are consumed just to produce ammonium,” explains the chemist.

The researchers have now developed a method to extract hydrogen straight from water splitting and deliver it to nitrogen. They achieved this by using a palladium (Pd) foil that functions both as an electrode and as a membrane.

“Palladium can serve as a membrane because it allows hydrogen atoms to pass through,” reports Kornienko. In the experiment, the Pd foil separated an anhydrous reaction environment, in which the LiNRR reactions take place, from a water-based reaction environment. “In the end, we were able to extract hydrogen atoms electrochemically directly from the water and transfer them to the reactive lithium/lithium-nitrogen material to produce ammonia,” says the chemist.

The researchers used infrared spectroscopy and mass spectrometry to confirm their method’s effectiveness. By employing a heavy hydrogen isotope (deuterium, D) as the water source, they produced ND₃ instead of NH₃. Conversely, when all molecules in the LiNRR compartment were labeled with deuterium, the system produced NH₃—not ND₃—just as intended.

Researchers File Patent Application

Bemana and Kornienko have already filed a patent application for this innovative process. While their experiments successfully produced ammonia (NH₃) using only electricity, there is still a significant challenge ahead: to make nitrogen fertilizer production economically viable from renewable sources, yields must improve by a factor of 1,000.

“We are still in the early stages,” says the chemist. “In general, research needs to be done on the reaction rates and selectivity of the system — the control of electrons to the desired target.”

The German Research Foundation (DFG) funded the project. The Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Bonn supported the publication.