At Summit, we often work with technologies that you can’t see with the naked eye. Seed coatings, polymers, and microbial inoculants may appear invisible once applied, yet they can determine how a crop performs in the field. Of these, rhizobia is one that continues to capture my attention.

Rhizobia is a genus of bacteria that lives in symbiosis with legumes like peas, beans, and alfalfa. When conditions are right, the bacteria colonize the roots and form nodules that pull nitrogen out of the atmosphere and convert it into a plant-available form. In return, the plant supplies sugars and carbohydrates to the bacteria. This partnership essentially allows legumes to fertilize themselves, reducing the need for added nitrogen and contributing to soil health.

Rhizobia presents a unique challenge in agricultural applications: it’s alive. Unlike chemical treatments, its viability isn’t easily visible or measurable once applied. Environmental factors such as heat, oxygen exposure, and moisture can gradually diminish bacterial populations. This uncertainty matters—because if rhizobia fails to establish a successful symbiosis with legume roots, the plants may struggle to access the nitrogen they need to thrive.

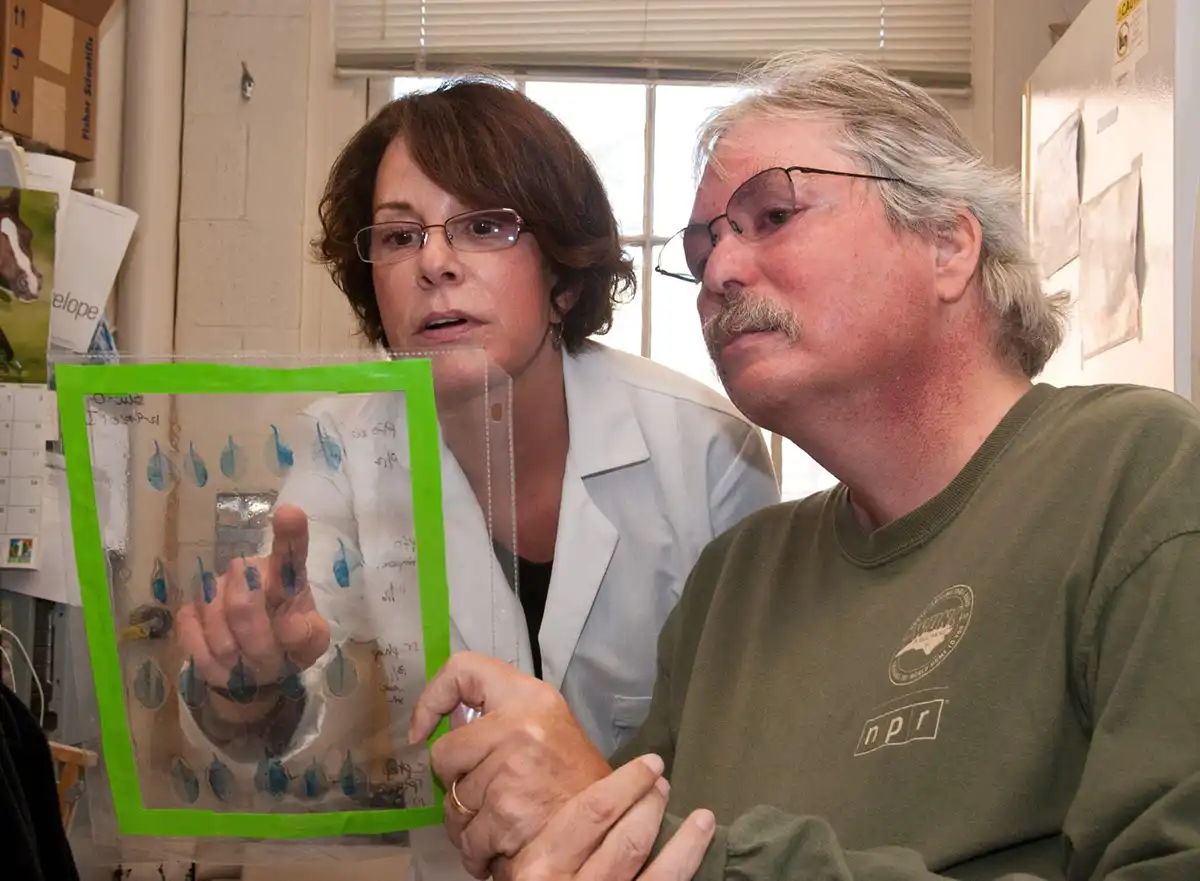

The Challenge of Measuring What You Can’t See

For most seed treatments, testing is straightforward. You can measure the concentration of a fungicide or verify a polymer coating with standard analytical methods. Biologicals are different. You can apply rhizobia at the time of coating, but verifying how many bacteria are alive weeks or months later is much less simple.

That has raised broader questions for me. How do we measure living technologies with the same rigor we’ve long applied to non-living ones? What does “quality assurance” look like when the input is a microbe, not a molecule? Rhizobia has become a useful lens for thinking about these questions — it represents both the promise and the complexity of biological innovation in agriculture.

Lessons from the lab to the field

As we’ve worked to better understand rhizobia, several lessons have become clear:

- Living organisms behave differently than chemicals. They have unique vulnerabilities and thresholds.

- Time matters. Even under careful storage, viability steadily declines.

- Context matters, too. Soil type, temperature, and planting conditions all shape outcomes.

- Testing is still evolving. Reliable, accessible methods for quantifying viable rhizobia on seed remain limited.

Each of these points underscores the same reality: biology adds a layer of complexity to seed technology. But complexity isn’t a drawback — it’s an opportunity to learn, adapt, and refine our practices. For me, exploring rhizobia has been less about finding easy answers and more about asking better questions, experimenting thoughtfully, and sharing what we learn. Because sometimes, the smallest organisms teach us the biggest lessons.