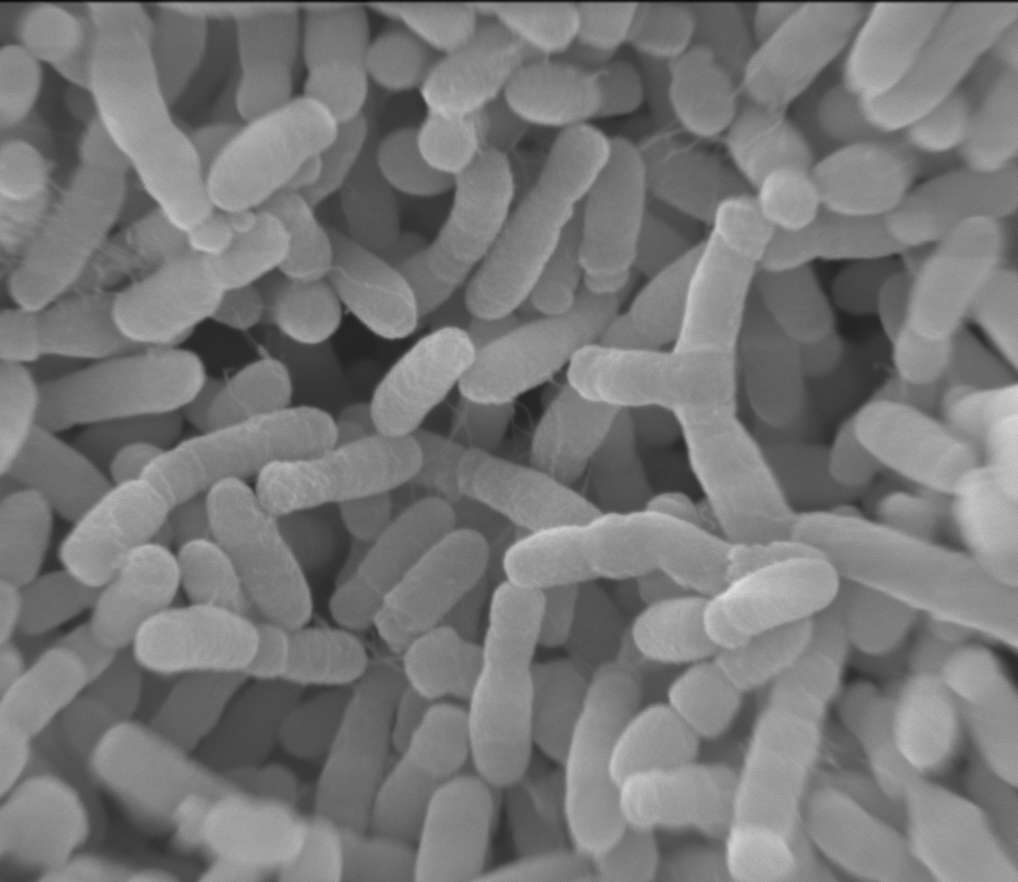

Researchers discovered that Agrobacterium tumefaciens—a workhorse of plant biotechnology—changes its infectiousness and resilience depending on how its chromosomes are arranged, revealing new insights for both crop innovation and disease control.

Depending on the setting, a crucial bacterium in biotechnology, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, can either damage crops or become a powerful tool for genetic enhancement.

New research from Iowa State University (ISU) shows that Agrobacterium’s ability to transfer DNA varies based on how its chromosome is arranged. Published in Science Advances, the study found that the bacterium infects plants more effectively when in its natural two-chromosome state. However, it grows faster and tolerates stress better when its genetic material is fused into a single, densely coiled chromosome.

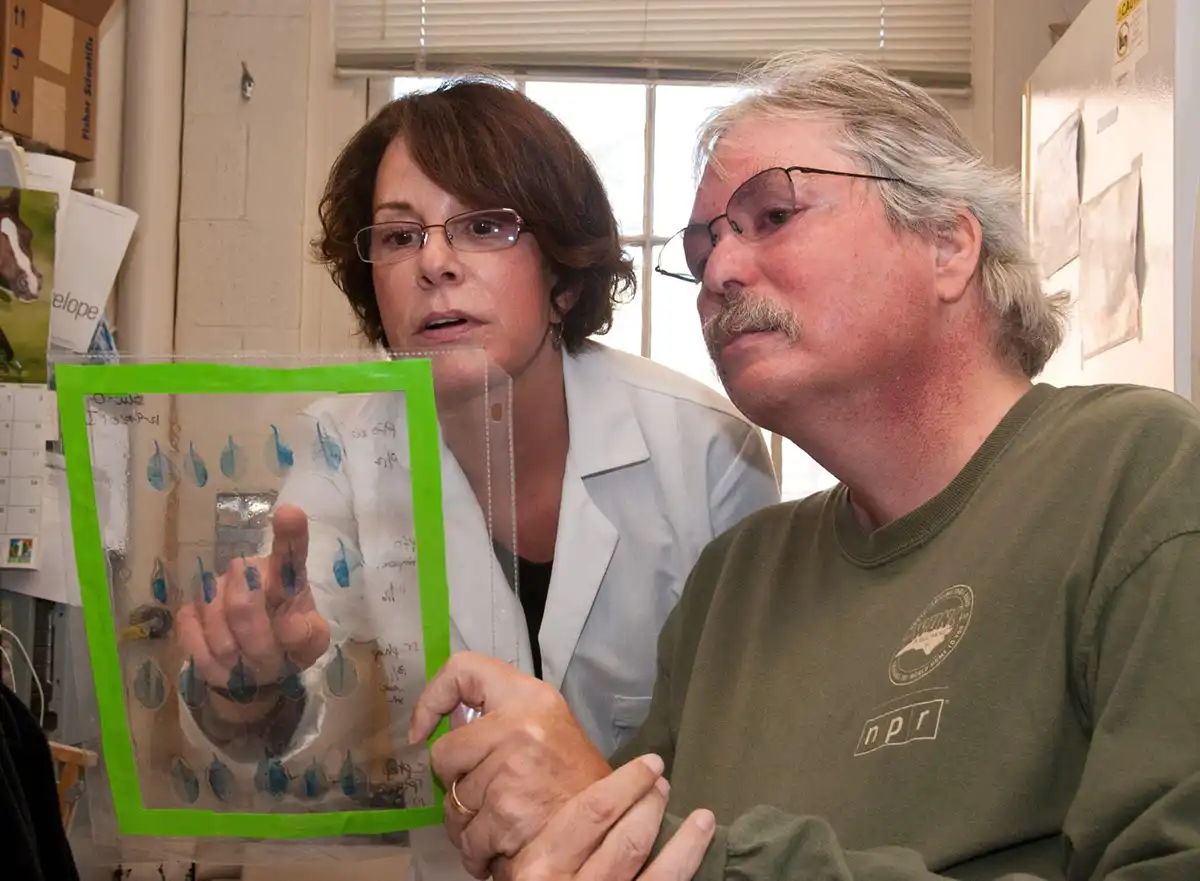

“Our work is the first to directly test how chromosome structure affects bacterial growth, survival, and ability to cause disease, and it opens the door for similar studies in many other microbes,” Kan Wang, Charles F. Curtiss Distinguished Professor of Agronomy and Global Professor in Biotechnology, said in an ISU news release.

Understanding how chromosome architecture influences Agrobacterium’s balance between fitness and infectiousness could help genetic engineers fine-tune its use for crop improvement or develop new defenses for plants susceptible to crown galls — the tumor-like growths caused on roots and stems.

A rare configuration

Agrobacterium is a soil-dwelling bacterium that infects crops such as fruit and nut trees, grapevines, and sugar beets. Since the 1980s, scientists have used its DNA transfer mechanism to insert custom genes into plants, enabling innovations like herbicide-tolerant soybeans, insect-resistant corn and cotton and vitamin-enriched Golden Rice.

While its role in plant biotechnology motivated the study, Wang said the team was equally intrigued by Agrobacterium’s unusual chromosomal configuration that includes both circular and linear shapes.

“This rare genomic architecture makes Agrobacterium an excellent model to investigate how chromosome shape and organization influence fundamental traits,” she said.

Some natural variants of Agrobacterium have a single fused linear chromosome. Using CRISPR gene-editing tools, the researchers created two additional strains with distinct chromosome setups: one version of the dual-chromosome type with both chromosomes circular, and one version of the fused strain with a single circular chromosome.

All four genetically identical types — differing only in chromosome configuration — were tested in the lab. The fused strains showed better growth and stress tolerance but were less effective at infecting plants.

Transcriptome analysis revealed why. The fused strains showed higher activation of genes linked to stress tolerance and survival, while the dual-chromosome strains had more active genes tied to virulence.

Far-reaching impact

For scientists using Agrobacterium in biotechnology, understanding these differences could improve precision, Wang said.

“It helps us fine-tune strains depending on our goals. We can keep the natural chromosome split for strong gene transfer into plants or use fused versions when growth stability is more important in the lab,” she said.

The findings also could inspire new ways to control crown gall disease by shifting pathogenic strains toward less virulent chromosome structures.

Future studies exploring how chromosome design affects other bacteria may even inform how infections are prevented or treated in humans.

“It also gives us a window into evolution, showing how bacteria adjust their DNA organization to adapt and thrive,” she said. “The impact of studying genomic architecture in the coming years could be far-reaching.”