Well-established in Europe and Australia, this protein powerhouse crop has gained a foothold in Canada. Is the U.S. next?

Across England, Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal and Australia, sweet lupin is a common crop. In Alberta Canada, government funding supports a small lupin research acreage. The crop may soon appear in some Northern areas of the United States as well.

There are, of course, good reasons for growing sweet lupin.

As a protein crop, sweet lupin is sweet indeed. Most importantly, it offers a similar protein percentage to soybeans, about 36%, with a complete amino acid profile. It also has lots of dietary fiber, very little starch, moderate levels (8%) of mostly unsaturated fat and moderate healthy carotenoids such as beta carotene.

With growing skill in the right soil and geographic area, sweet lupin can achieve comparable yield to field peas. The two crops both favor regular rain and not too much heat. Alkaline soils are a no-go for lupin: Soil pH must be less than 7.8 or 7.4, depending on the variety.

It’s also a good rotational choice. Tristan Choi, a researcher dedicated to lupin research in Canada, says that as a legume, sweet lupin fixes nitrogen but provides another important benefit.

“Independent research has found that our lupin varieties are resistant to Aphanomyces root rot, which can dramatically reduce yield in field peas and some other pulse crops,” says Choi, who is at the helm of Lupin Platform Inc., the Canadian company in its fourth year of developing the lupin value chain. “Faba beans are also resistant to this pathogen, but sweet lupin may be able to be grown in areas where faba beans cannot.”

LPI has Canadian registration for three European varieties bred and has exclusive distribution licenses for North America. Although the flower color tends to shift throughout the growing season, one is known as a white variety (Lupinus albus) and called Dieta. The others are blue varieties (L. angustifolius) called Boregine and Lunabor. Choi explains that at this point, all are considered food-grade varieties but feed uses are planned for both as well.

Red River Seeds and JS Henry and Son in Manitoba are multiplying Dieta. Boregine and Lunabor seed production is taking place at Galloway Seeds, Lindholm Seed Farm and Brian Ellis Seed in Alberta.

Lupin’s Journey in Canada

Sweet lupin was first discussed about two decades ago in Alberta when researchers, agronomists and others looked at trying European varieties. A team at Alberta Agriculture determined they could easily grow the crop in the province, but the lack of a market precluded much further study. With renewed interest in 2010, researchers began new investigations. Then, seven years later, increasing consumer interest in plant-based foods prompted another look at high-protein lupins. Limited studies ensued with Boregine.

Since 2021, Robyne Bowness Davidson, who was at Alberta Agriculture and is now a pulse research scientist at Lakeland College in Lacombe, Alberta, has led a three-year project studying various lupin production and agronomy challenges. These include broadleaf herbicide options, disease and insect control and the best way to achieve pre-harvest dry-down.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research scientist Breanne Tidemann is also evaluating herbicide options for lupins, with funding from Alberta Pulse Growers. This group is also funding protein and starch research.

“Lupin has great potential for protein fractionation for the food market,” says Bowness Davidson. “But it’s also suitable for livestock feed and it’s mostly used for feed in Europe and Australia. Lupins are very exciting to me because they can be grown in some areas of Western Canada where we cannot grow soybeans due to the climate.”

North American interest in lupin is slowly spreading beyond Canada. Bowness Davidson reports a small but notable flame of U.S. interest in sweet lupin, with several breeding companies making inquiries.

“We’re making a lot of progress here that they can build on, but many areas where they grow soybeans won’t be suitable because lupin doesn’t like heat.” she says.

Choi is collaborating with University of North Dakota scientists on a small lupin trial.

“The flowers will abort (due to heat). And high alkaline soils result in total crop failure. So, there’s potential in the U.S. but only in select areas.” Choi reports.

He said the results are not yet available.

But while potential exists for lupin to become a more widely grown crop in Canada and into the United States, Bowness Davidson stresses there’s a lot of work left to be done.

“We have some varieties doing very well but others not,” she reports. “We must figure out weed management. It’s the number one constraint for yield. We don’t have a lot of products at our fingertips so we’ll continue to work diligently and build on what we’ve learned. Disease management is going well and hopefully, that won’t change. Insects have not been a concern in the past but this year, blister beetle showed up.”

Milling and Markets

LPI continues its work developing the entire lupin value chain. Choi has a core team of six, and hires about 12 field associates and project managers each year to provide seasonal advice to his contracted growers.

Currently LPI ships seed to a Minnesota mill for various U.S. customers making high-protein ‘keto’ pasta, beverage mixes and more. In Canada, Choi uses a mill in Saskatchewan’s capital city, Saskatoon, but he is now retrofitting a mill he recently purchased in Swift Current, a smaller city in that province’s south.

“This will allow us to scale up,” he explains. “We are very mindful of how we grow. We stay focussed on our small group of about ten customers. Each is unique in their needs for a customized product, for example steam-treated or heat-treated forms. On the feed front, we’ve run a feed trial on an Alberta dairy farm with lupin meal instead of canola meal, and interim results for butterfat and milk yield are very positive.”

He hopes the results will lead to a graduate student doing a two-year study.

After limited acreage three years ago, LPI contracted 680 acres and milled about 160 tonnes in 2022. This year, acreage is 1,000 acres, mostly in Alberta with some in Manitoba. Next year, the target is between 1,200 and 1,500 acres with LPI’s small group of select growers.

Meanwhile, Choi is keen to collaborate with breeding companies and/or customers in Europe, Australia, the United States, Argentina and beyond.

“The future looks fantastic for lupin,” he says. “We will continue to grow slowly and wisely and work with our selected growers and talented agronomists. We’re also marketing our own food products, with R&D supported in part by the [Canadian] federal government.”

He adds that LPI will launch lupin pickles next year and continues to explore ice cream and other products.

“The batch we made with the famous Bridge Drive-in ice cream shop in Winnipeg sold out this summer and the traction got the attention of national news outlets. I hardly got to try any of it” he adds.

Alkaloid Removal From Other Lupin Species

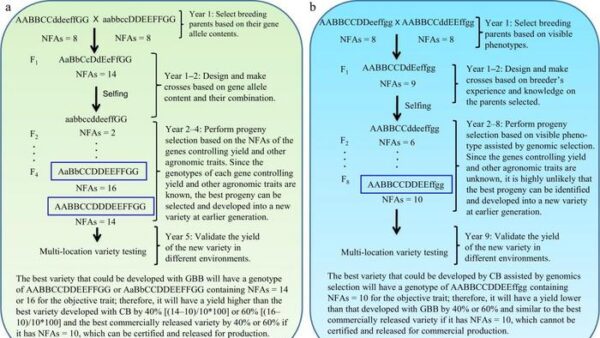

Although breeders have been making progress with reducing alkaloid levels in sweet lupin varieties discovered almost a century ago, only recently has the biochemistry of alkaloid production in the lupin taken a huge leap forward. Two enzymes involved in alkaloid synthesis had been identified, but a team at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark discovered a third acetyltransferase enzyme.

Team leaders Fernando Geu-Flores and Davide Mancinotti compared L. albus varieties with both high and low alkaloid levels and narrowed their focus on a mutation that must exist to prevent alkaloid production in the sweet varieties. Geu-Flores and Mancinotti then approached a Danish firm called Traitomic (a spin-off of Carlsberg Brewery) to create a similar mutation in L. angustifolius through chemical mutagenesis. This traditional breeding technique is exempt from the European Union regulations that ban other types of genetic modification such as gene editing.

Traitomic developed a platform of more than 100,000 genetically-different lupin variants and using their FIND-IT technology, they were able to identify a plant with exactly the right change in the acetyltransferase gene. Traitomic team leaders Gustav Hambraeus and Toni Wendt note that the full process, from the initial request to the handover of the specific lupin variant, took less than a year. And, with the lupin platform established, Traitomic could also deliver many other specific gene variants requested by the University of Copenhagen in just a few weeks.

Further work with this gene mutation should enable researchers to reduce alkaloid production in other species of lupin with even higher protein contents than existing cultivated varieties (such as L. mutabilis, or Andean lupin).

Exploring the World of Lupin

Don’t confuse lupin with its poisonous ornamental cousin the bluebonnet. Today’s lupin varieties have relatively low levels of the alkaloids that are present in historic and wild lupin genotypes. These varieties were first discovered in Europe in the 1930s and were bred into what’s properly referred to as sweet lupin. However, it’s also a cousin to peanuts and therefore may cause anaphylaxis in allergic individuals.

A Rich History

-The oldest lupin seeds were found in Egypt, dating back to the 22nd century B.C. They spread to other areas of the Mediterranean and beyond during the Roman empire. In North America and Latin America, lupin seeds were a common food in the time of the Incan Empire and were also consumed by Native American tribes such as the Yavapai.

-Lupin seeds are still eaten as a traditional pickled snack food in the Mediterranean, Latin America and North Africa.

-For thousands of years, consumers had to soak the seeds for a week because of their high alkaloid content.

-In the 1930s, lower-alkaloid varieties appeared in Europe, allowing breeders to make advances with ‘sweet lupin’ and enabling large-scale cultivation.

A Staple and a Delicacy

-Up until a few years ago, the vast majority of lupin grown worldwide went to livestock feed. However, lupin use in food products is now expanding due to strong demand for plant-based protein.

-Today, bakers and cooks in parts of Europe and Australia add lupin flour to baked goods, pancakes, and more to increase flavor and protein and to provide a creamy color. Many companies are exploring incorporating lupin in beverage powders and other high-protein products.