Using endophytes as seed treatments in agriculture is a relatively new concept. At JABB of the Carolinas, we often hear questions about how and why Beauveria bassiana performs the way it does. I find it useful to look first at endophytes broadly before diving into specific examples. There are layers of understanding. At the surface level, you understand what an endophyte is and you see the results in the fields. One layer deeper, you begin to understand where different endophytes operate in the plant and how combining them is beneficial. At the deepest level, you see the biological processes that make those results possible.

To start with a basic definition, an endophyte is an organism that lives within a plant without causing any harm. In many cases, there is also a benefit to the plant, which is why certain endophytes become useful in agricultural settings. Common benefits include improved seedling emergence, stress tolerance, and improved overall plant health. These benefits translate into risk reduction, increased yield and improved financial returns for producers.

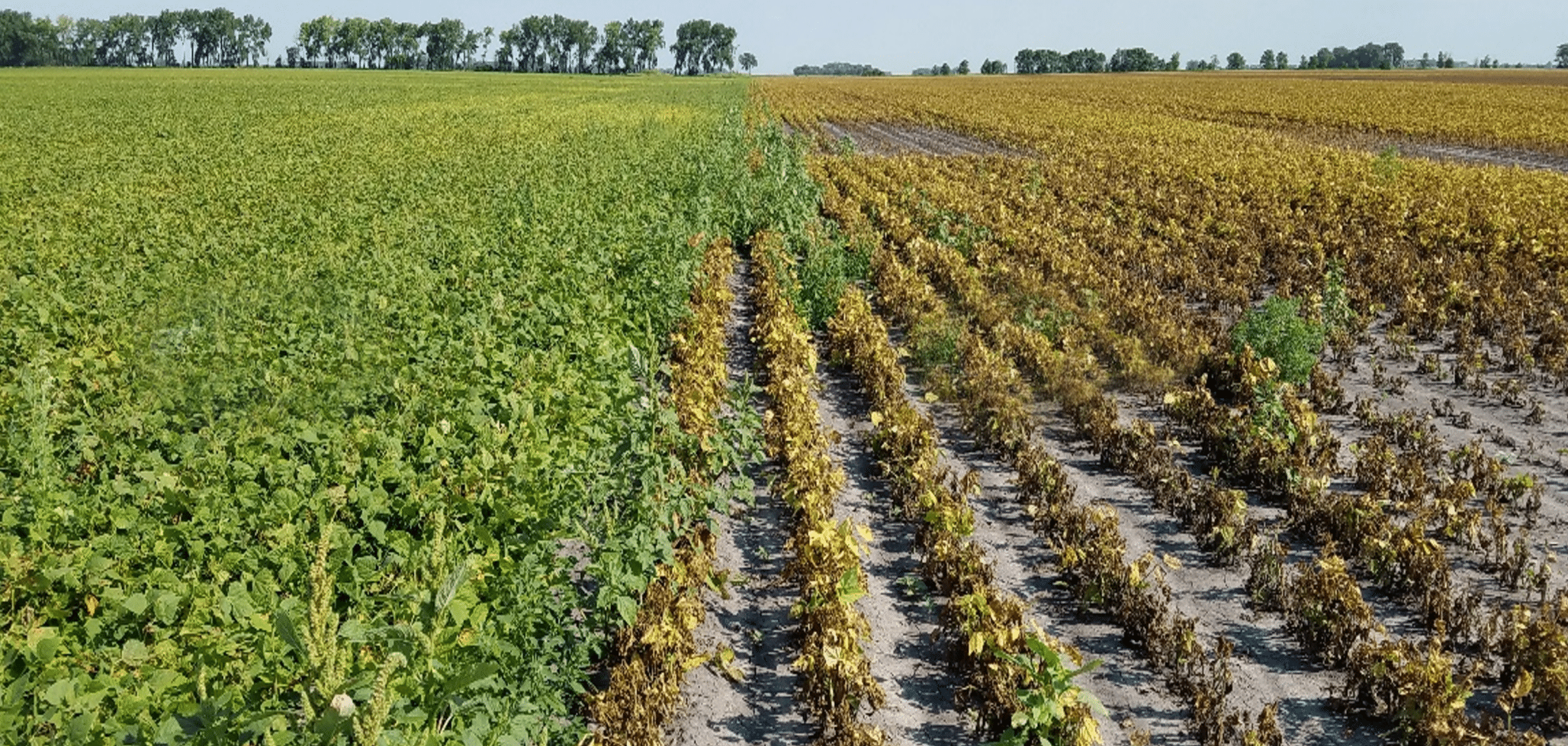

When we go one layer deeper, differences between endophytes start to matter. Many endophytes provide similar benefits, but they operate in different parts of the plant. Trichoderma, for example, functions primarily in the root zone. Beauveria bassiana, on the other hand, is a systemic endophyte. It colonizes the entire plant from root to tip and remains with the plant through the growing season becoming a valued symbiont to the plant. When endophytes with different regions of activity are used together, their combined effect can be greater than what would be expected from each one individually.

In my previous article on pairing biologicals, I explained how we have had a preliminary trial of B. bassiana with another biological. While results aren’t finalized, I can share that with just B. bassiana we saw a 6% yield increase and with the other we saw a 4% yield increase. While simple math might tell us this will mean 10% if we combine the two, we actually saw 12% along with other improvements in plant performance beyond what would be expected.

If we dig a little deeper, we see exactly how endophytes support the plant.

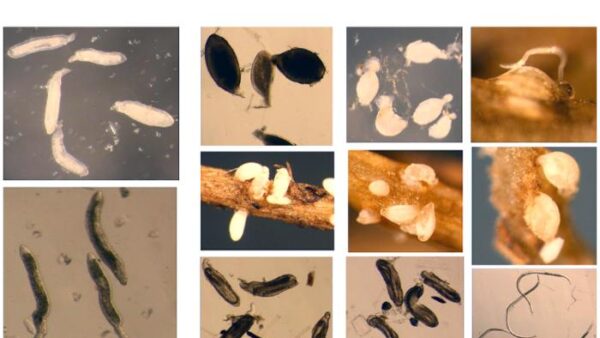

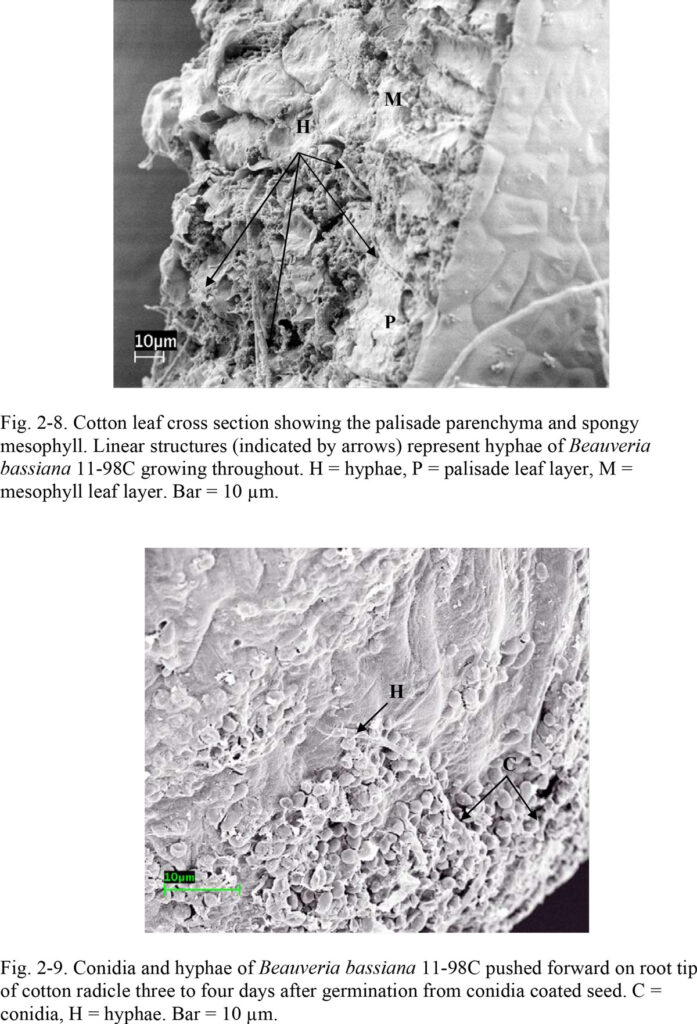

Endophytes are most commonly applied as a seed treatment. They are very stable in this form and store well, and in the case of B. bassiana, it puts the treatment exactly in the right place. When the spores come into contact with an emerging root, that contact triggers the spore to germinate and send out a germ tube that enters the plant tissue and begins forming a mycelial network. This network is made up of fine filaments of the fungus that weave around the plant’s cells without damaging them. Once established, this living web can move nutrients, produce beneficial compounds and communicate signals throughout the plant.

Once established in the plant, endophytes get to work. They work with the plant to produce phytohormones, which are plant-like hormones, like auxins, that influence growth and development, resulting in a larger root network and vigorous growth. They can also make nutrients like phosphorus and iron more available to the plant by increasing their solubility.

While seed treatment is considered the optimal way to apply B. bassiana, it can also be applied as a root drench or foliar treatment. I have been asked if there’s value in applying additional B. bassiana later in the season, and I have always said that seed treatment is enough. However, we continue to learn. In a small test this year, a seed treatment followed by foliar application six weeks later resulted in double the response we expected. Further testing is needed, but it shows me that we’re always going to be surprised by what endophytes can do.

If you have any questions about how endophytes work, or how they might add value to your seeds, please reach out. I can meet you at whichever layer of understanding you want.