In an unpredictable world, farm success will rely on resilience. There are plenty of factors farmers won’t ever control — the weather, volatile input costs, tariffs, and market uncertainty. All of these have impacted modern agriculture, but building resilience mitigates their damages. For growers, a crop’s ability to recover and deliver yield under diverse and unpredictable stresses, is central to risk management.

Yet resilience remains difficult to measure and manage. Yield gains are straightforward to quantify and market, but yield stability and loss avoidance, especially under biotic stresses such as disease pressure and abiotic stresses such as drought, heat, or nutrient limitation, can only be assessed over time. They emerge across seasons, environments, and stress combinations. From a risk perspective, yield loss in any given season is a function of the probability of a negative event multiplied by the magnitude of its impact. While growers have limited control over weather or disease events, resilience directly targets impact—reducing severity, shortening recovery, and stabilizing performance when stress occurs.

Crop genetics play a critical role in this equation by embedding resistance and tolerance traits directly into the plant. But genetics alone are not sufficient. There is a second, often underappreciated driver of crop resilience: microbes.

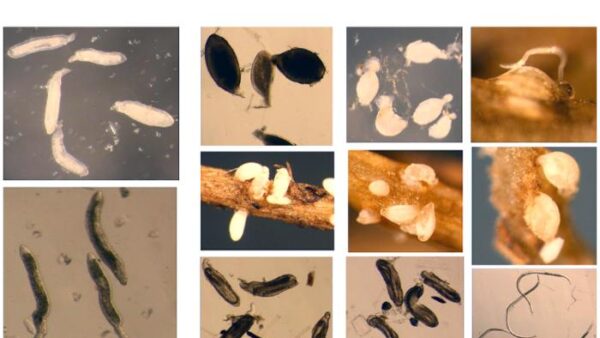

Plants have always relied on microbes to survive and function in stressful environments. Photosynthesis itself is enabled by an ancient bacterial ancestor embedded in plant cells. The successful colonization of land by plants depended on microbial partners capable of nitrogen fixation, phosphorus and micronutrient solubilization, extensive fungal networks for nutrient capture, and protection against drought, salinity, and temperature extremes. In return, plants provide carbon-rich habitats for microbial communities. Despite this deep evolutionary partnership, modern agricultural practices have frequently disrupted or decoupled key plant–microbe relationships, compromising system resilience.

Microbial inoculants offer a pathway to restore and strengthen these beneficial interactions. Well-characterized microbes can enhance nutrient acquisition and use efficiency, stimulate root growth, activate stress-response pathways, and improve tolerance to drought and salinity. Importantly, microbes can help plants manage multiple simultaneous stressors and accelerate recovery when favorable conditions return. Certain microbes also protect against pests and pathogens through diverse and complementary mechanisms. These benefits are not universal—microbes are not a one-size-fits-all solution—but when matched correctly to crop, soil, and environment, and each other they can meaningfully improve yield stability.

Resilience should be a primary performance metric, and it is incumbent on the biologicals industry to document the key role of biologicals in supporting crop resilience and reducing yield variability. Microbial solutions can go where chemistry alone cannot—working within plant and soil systems to buffer variability and manage uncertainty. The key question shifts from “How many bushels will this add?” to “Does this technology reduce variability, protect yield under stress, and complement my production system?”

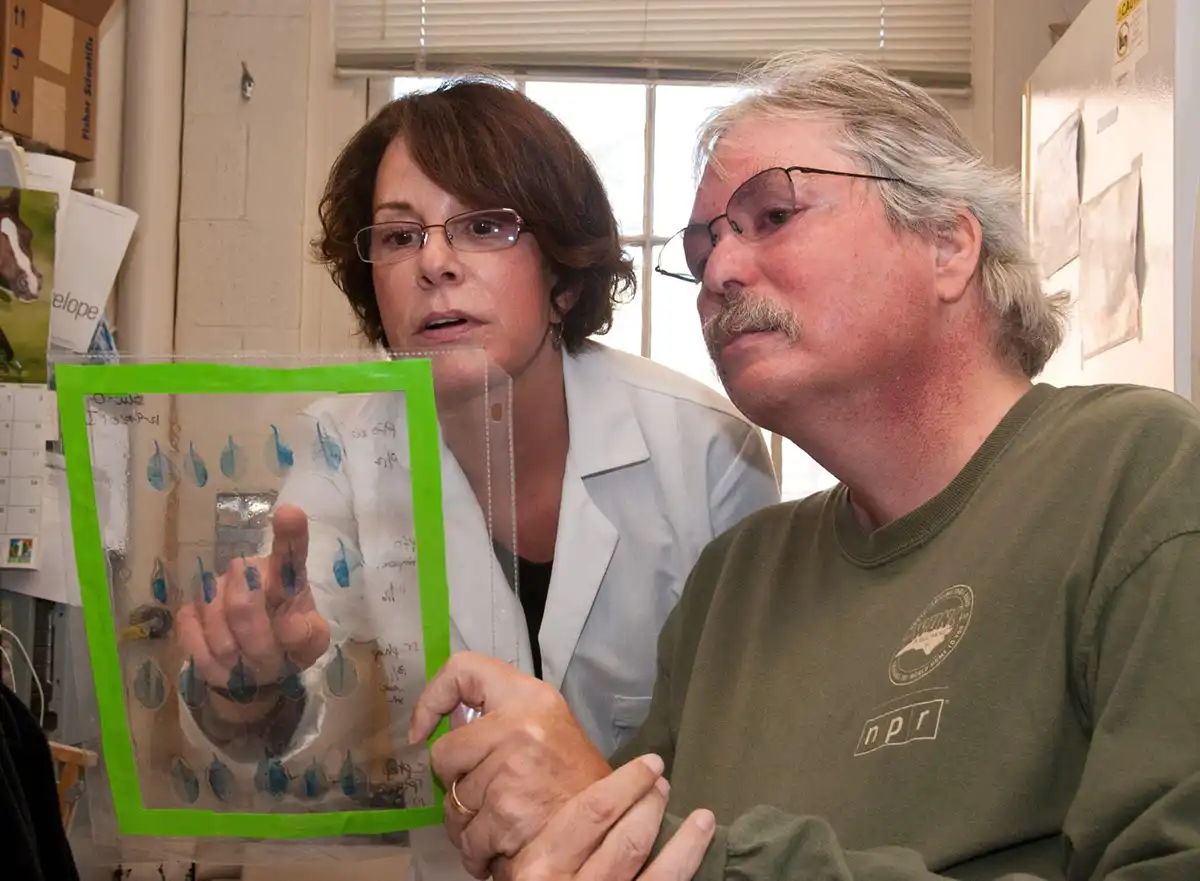

Farmers need systems that do more for them, products that enhance both biologicals and chemistries, and companies that can meaningfully innovate. At Jord BioScience, we are focused on redefining how microbial inoculants are evaluated and deployed, grounding their value in measurable contributions to crop resilience and long-term performance in an increasingly unpredictable world.