New molecular insights into plant decision-making could shape the next generation of seed traits for a hotter, drier world.

Plants may look quiet, but inside their leaves, there’s a constant negotiation underway — one that can mean the difference between growth and drought-induced death. Penn State University professor of plant biology Sarah Assmann is leading a new study that finally reveals the molecular messengers that coordinate this life-critical conversation.

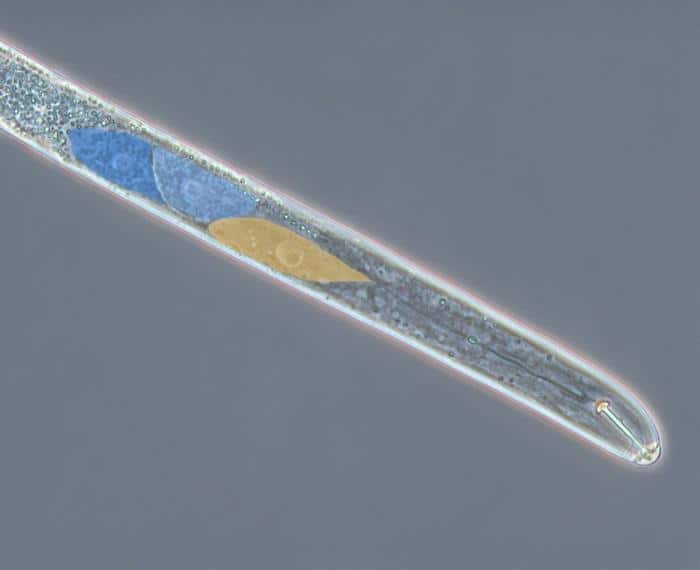

Published in Nature Plants, the research uncovers how sugars and maleic acid act as internal signals, telling specialized guard cells when to open the plant’s stomata, the microscopic pores that let in carbon dioxide for photosynthesis but also release water vapor. The findings solve a decades-old biological mystery and could reshape efforts to improve water use efficiency in crops, especially under climate stress.

“This discovery significantly advances our understanding of how plants coordinate their internal metabolism — the chemical reactions they use to make energy — with their external environment,” says Assmann. “Our findings open doors for future research into improving plant resilience and crop yields.”

For seed developers and breeders, the breakthrough offers a novel pathway to enhance drought tolerance and optimize water use in key crops — priorities that have grown urgent under shifting climate conditions.

A Mystery 40 Years in the Making

Assmann first became intrigued by the idea of an internal plant “messenger” when she was a graduate student in the 1980s. Though researchers had long known that light triggered stomatal opening, there was also evidence of a chemical cue coming from within the leaf.

“I had been intrigued since I was a graduate student in the 1980s of evidence in the plant physiological literature that such messengers existed,” she says. “Advances in metabolomics convinced me that the necessary mass spec techniques were now available to catalog the apoplastic metabolome, thereby identifying candidate mesophyll messengers that could then be tested by other techniques to determine whether or not they played a messenger role.”

What followed was a global collaboration and a team that extracted apoplastic fluid, the liquid between plant cells, from Arabidopsis and fava bean leaves exposed to red light and darkness. They identified 448 unique metabolites, including sugars and maleic acid, which increased in light conditions.

That knowledge gives the seed industry a new set of physiological and molecular markers that could be used to screen germplasm or develop traits related to stomatal efficiency. Understanding how internal metabolites guide stomatal function can complement conventional breeding and biotech approaches that seek to enhance photosynthesis, water retention and yield stability.

Unlocking a New Trait Target for Seed Innovation

“Plant biologists have an identified set of plant hormones,” Assmann says. “An interesting question for future research is whether any of the ‘non-hormone’ metabolites that we identified in apoplastic fluid are actually playing a role as plant hormones, in addition to their recognized function, analogous to sugars being both signals and a source of energy.”

What allowed this research to succeed where others had stalled was its scope.

“What really allowed us to make this advance was the collaborative effort of many different laboratories across the globe, each with their own area of expertise, which included metabolomics, biochemistry, electrophysiology, and plant physiology,” she says.

By carefully isolating the epidermis and exposing it to sugars under red light, the researchers demonstrated that sugars promoted stomatal opening. Follow-up experiments showed how sugars influenced carbon dioxide uptake and water loss, painting the first complete picture of how these internal messengers drive stomatal behavior.

For seed companies, these results provide a clear, testable mechanism to influence a trait that has always been difficult to breed for: the balance between carbon gain and water loss. With climate variability putting pressure on water availability, the ability to identify or engineer lines with more precise stomatal control could offer major agronomic advantages.

What It Means for Real-World Crops

Importantly, the team demonstrated that the identified messengers function not only in model plants but also in crop species like fava beans. That opens the door for broader agricultural applications.

“It is notable that we demonstrated that these messengers function not only in the ‘model’ plant Arabidopsis but also in a crop species, fava beans,” Assmann says. “This suggests a commonality of function across plant species. Understanding these messengers — and potentially elucidating others — could help in the creation of crops with improved water use efficiency.”

The discovery could also improve phenotyping technologies. With 448 metabolites now cataloged from apoplastic fluid, researchers and breeders have a new set of potential biomarkers for screening stomatal behavior and stress resilience. These biological insights could be integrated into digital platforms and predictive models for faster trait evaluation — streamlining the seed development pipeline from lab to field.

“We’re focused on understanding how plants sense and respond to environmental conditions,” Assmann says. “Plants can’t uproot themselves and find somewhere else to live; they have to deal with whatever the environment throws at them — increasingly drought and heat stress — so we study what makes plants resilient, from the very specific molecular level all the way up to whole plant physiology and field experiments, with the goal of improving crop productivity.”

Next Up: Smarter Guard Cells

The discovery of sugars and maleic acid as messengers has opened a new field of questions for Assmann’s lab. One major focus now is how guard cells integrate multiple types of environmental signals beyond light — such as humidity, carbon dioxide concentration and drought-related hormones.

By solving one of plant biology’s longest-running mysteries, Assmann and her colleagues are laying the groundwork for a future where crops are not only more efficient but also more resilient — a vital goal for seed companies and growers alike.

Yotam Zait performed extensive experiments for the Nature Plants article as a post-doc in her lab. The team then performed additional experiments after Zait began his position as an assistant professor at the Hebrew University, Faculty of Agriculture, Rehovot, Israel.

“In regions where water is the main limiting factor for agriculture, understanding how plants fine-tune the balance between carbon gain and water loss is key to ensuring future food security,” Yotam says.

Assmann says the next big question is how guard cells integrate these mesophyll messenger signals with other signals that this specialized cell type also perceives.

“An analogy would be if cells in the retinas of our eyes could not only ‘see’ but also ‘taste’ and ‘smell,’” she says. “How guard cells integrate all this information in the regulation of stomatal apertures is an ongoing question that has fascinated stomatal physiologists for years.”

As the seed industry looks for deeper biological understanding to support next-generation traits, discoveries like this offer a rare combination of scientific elegance and practical relevance. Whether used to engineer new varieties, speed up trait selection or build more climate-adaptive cropping systems, the molecular messengers identified in this study could help determine how — and whether — crops thrive in the decades to come.

The Penn State team included doctoral student Yunqing Zhou, Associate Professor of Biology Timothy Jegla, and postdoctoral scholars Mengmeng Zhu and Additional collaborators came from institutions in Japan, Israel and the University of Mississippi. The U.S. National Science Foundation funded the Penn State portion of the research.