Even with CRISPR and advanced sequencing, altering plant behavior remains labor-intensive. A new approach aims to reveal how gene expression is actually controlled.

What Was the First Edit?

Agriculture, from the outset, has depended on humans shaping plant genetics to encourage faster growth, higher yields and greater tolerance to drought, pests and disease. For thousands of years, that work happened through selective breeding. More recently, it expanded into genetic engineering. Yet even with ultra-fast sequencing technologies and CRISPR-based gene editing tools, successfully changing how a plant behaves remains a slow, labor-intensive process.

Scientists at the Joint BioEnergy Institute are working to accelerate that timeline with a new technology called ENTRAP-seq, which can simultaneously screen thousands of transcription regulators in plants. Transcription regulators are proteins that control how genes are expressed, functioning much like dimmer switches. They can shut a gene off entirely or fine-tune how much of a specific product a cell produces by influencing how often DNA is transcribed into RNA.

Many of the enhanced traits found in today’s crop and biofuel species result from this type of transcriptional modulation. Thousands of years ago, farmers unknowingly selected wheat varieties with higher expression of genes controlling grain size. Modern agricultural scientists want to better understand and control these genetic switches, but despite decades of genome research, that knowledge remains limited.

The Bottleneck Isn’t Editing — It’s Control

“Even for well-studied plants, where we know which genes control which traits and often how those genes work, it’s still not clear how to change gene expression in a way that leads to beneficial outcomes,” Simon Alamos, a postdoctoral fellow at UC Berkeley and JBEI, said in the news release. Alamos is co-first author on a study describing ENTRAP-seq, now published in Nature Biotechnology. “We want to use plants’ own transcription regulators, as well as proteins from other organisms like plant viruses, but until now we didn’t have a way to predict what they do or test them quickly.”

While gene editing tools have become faster and more precise, the ability to understand how genes are regulated, and how those controls interact across complex networks, has lagged. That gap has made it difficult to reliably translate genetic insight into improved plant performance.

How Do We Go From Whole Plants to Single Cells?

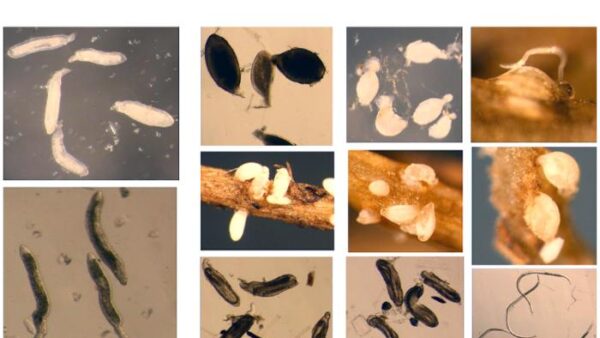

ENTRAP-seq addresses that limitation by shrinking experiments that once required entire plants or leaves down to individual cells. The method uses a plant-infecting bacterium to deliver DNA sequences encoding potential transcription regulator proteins into a leaf, alongside an engineered target gene.

Researchers create a library of thousands of bacteria, each carrying instructions for a different protein variant. When the library is injected into a leaf, each bacterium transfers its genetic material into a single plant cell. As a result, thousands of distinct protein variants are produced across individual cells within the same leaf.

Once inside the cell, these protein variants interact with molecular switches in the nucleus, revealing whether they act as activators or repressors. If a variant activates gene expression, the engineered target gene produces a protein designed to bind to magnetic tags. Researchers then use magnets to isolate the cells that express the target protein, sequence their DNA and match the results to the original list of introduced protein variants.

Thousands of Switches, One Experiment

After establishing the approach, the team demonstrated its speed using a transcription activator known to regulate flowering time in Arabidopsis, a common model plant. They created 350 mutant versions of the protein and rapidly screened which variants increased or decreased flowering.

“This experiment took just a few weeks,” says lead author Patrick Shih, deputy vice president of the Feedstocks Division and director of Plant Biosystems Design at JBEI. “In a previous study, our team analyzed the activity of about 400 plant transcription regulators using traditional methods. That effort required two people working full time for two years.”

To generate candidate activator designs for the study, Shih’s team used an existing AI model that predicts DNA sequences capable of encoding gene-activating proteins across different organisms.

“The model helped us focus our experimental work on the most informative proteins drawn from thousands of genomes,” says co-first author Lucas Waldburger, a graduate student researcher at UC Berkeley and JBEI.

That model’s accuracy, however, has been limited by the lack of available training data. Historically, studying transcription regulators has been slow and resource-intensive. ENTRAP-seq changes that by enabling researchers to generate large datasets quickly, which in turn can improve predictive models. As those models improve, scientists can more easily scan plant genomes to identify where gene switches are located, information that remains sparse for many species.

“We’re trying to find all the switches and understand whether they turn things up or down,” Shih says. “We also want to know how much range each switch has. Building that catalog would be a major advance. From there, we might identify switches that influence plant size, yield or stress tolerance, and then ask how far we can adjust them.”

ENTRAP-seq is available for licensing through Berkeley Lab’s Intellectual Property Office. The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is focused on discovery science and solutions that support abundant, reliable energy. Its research spans materials, chemistry, physics, biology, earth and environmental science, mathematics and computing. Founded in 1931, the lab is managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, and its scientists have been recognized with 17 Nobel Prizes.