Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is no longer a fringe idea.

Airlines want it. States are building policy around it. Researchers are racing to lower costs. The next question is what it means for seed companies, breeders and the agricultural value chain that will ultimately supply it.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel Pushes Agriculture Into Aviation’s Supply Chain

Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is often framed as an energy transition story. In practice, it is becoming an agriculture story just as quickly.

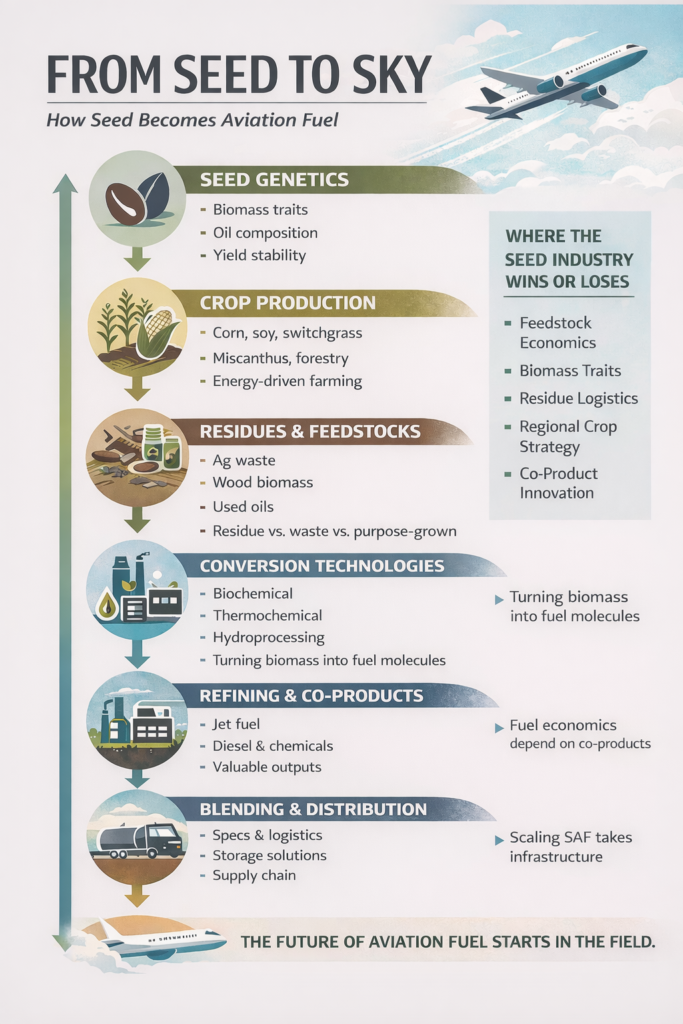

The aviation sector is trying to replace petroleum-based jet fuel with alternatives that meet the same performance standards without requiring new aircraft, engines or fueling infrastructure. That constraint immediately pulls agriculture into the conversation. SAF must be produced from hydrocarbons found in biological materials, including crop residues, forestry byproducts, waste streams and purpose-grown biomass.

Commercial Aviation Alternative Fuels Initiative (CAAFI) executive director Steve Csonka describes the scale of the shift.

“We’re talking about really a new industrial sector that we’re trying to bring online to produce more sustainable fuels for aviation,” Csonka said in a press release.

Progress is real. SAF has moved beyond pilot projects and into commercial delivery at multiple airports. But the conversation inside the industry still revolves around one persistent barrier: economics.

Price Still Determines How Fast SAF Scales

The aviation sector knows how to produce sustainable aviation fuel. The problem is making it affordable enough to compete with petroleum-derived jet fuel.

“The key issue is that they are still not very affordable,” Csonka says, noting the continued price advantage of conventional jet fuel.

Production capacity exists and continues to grow, yet not all of it is being utilized. Market signals, policy structures and competing renewable fuel pathways influence whether producers target aviation fuel or shift production toward markets such as renewable diesel.

That reality reshapes how agriculture fits into the story. Feedstock availability alone does not determine adoption. Feedstock cost, conversion efficiency, supply chain logistics and policy incentives all influence whether SAF becomes a durable market.

How Do Feedstocks Move From Concept to Farm-Level Reality?

The SAF conversation quickly narrows to the question agriculture understands best: what raw materials can be produced consistently, aggregated efficiently and converted economically.

Elvis Ebikade, director of aviation, Bioleum Corporation, says the pathway to fuel production is inseparable from the characteristics of the feedstock, adding that those technologies are primarily tied to the feedstocks.

Current commercial SAF pathways rely heavily on oil-based inputs such as used cooking oils and vegetable oils. Emerging technologies are pushing into lignocellulosic materials, including crop residues and woody biomass, with the goal of expanding supply and lowering costs.

But abundance on paper does not guarantee practicality.

“On paper, corn stover is abundant,” Ebikade says. “In practice, it is very hard to work with, because it has a lot of ash.”

That ash can disrupt conversion processes and increase processing costs. The same challenges appear across multiple biomass streams, reinforcing a familiar lesson for the seed and breeding community: biological systems introduce variability, and variability affects economics.

Co-Products And Conversion Technology Shape The Economics

The long-term viability of sustainable aviation fuel may depend less on fuel alone and more on the broader value created from each ton of biomass.

Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center director and University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Bacteriology professor Timothy Donohue, emphasizes that fuels and chemicals must be developed together.

“Only half of their profit comes from fuels. The other half comes from chemicals,” he says, describing petroleum refinery economics and the model bioenergy researchers are working to replicate.

Research teams are exploring ways to convert lignocellulosic biomass into both fuels and chemical intermediates used in materials, plastics and industrial applications. That approach improves the financial case for biorefineries and creates additional markets for agricultural byproducts.

Donohue summarizes the goal as simply converting residues into revenue.

He says for seed companies and crop scientists, that framework signals a new set of opportunities. Traits, crop systems and residue-management strategies that improve biomass quality and conversion potential could directly influence SAF economics.

State Policy Drives Early Market Development

Policy is accelerating the conversation, particularly at the state level. Clean Fuels Michigan executive director Jane McCurry says uncertainty around federal policy has pushed states to take a more active role in building incentives and market frameworks.

“There’s a huge opportunity for states and regions to step up and create certainty at the state level,” she says.

Michigan is pursuing both a sustainable aviation fuel tax credit and a broader clean fuel standard designed to reward lower-carbon fuels across multiple sectors. The goal is to attract investment, support agricultural supply chains and position the region as a production hub.

The economic implications are substantial. Modeling tied to clean fuel policy proposals in Michigan estimates billions in potential investment and economic activity over time.

For agriculture, those policies translate into demand signals. Domestic feedstock provisions, regional production incentives and partnerships with airlines all point to a future where crop systems and biomass supply chains are directly tied to aviation fuel markets.

Infrastructure And Blending May Become The Next Bottleneck

As production increases, logistical constraints begin to surface.

Fuel blending, storage and distribution systems built around petroleum must adapt to accommodate multiple SAF pathways and specifications. Even when fuels meet standards individually, blending can introduce new challenges.

“You might actually blend synthetic fuel and jet fuel… and they give you an off spec fuel,” Ebikade says.

Scaling SAF will require coordination across refiners, midstream operators, airports and producers. The seed industry has seen similar coordination challenges before when new traits or technologies require synchronized adoption across the value chain.

The Food Versus Fuel Debate Still Shapes Public Perception

Public perception continues to influence how SAF is discussed, particularly within agriculture.

Concerns about diverting food crops into fuel production surface frequently, even as industry participants emphasize the diversity of feedstocks under consideration. Agricultural residues, forestry byproducts, waste streams and purpose-grown energy crops are all part of the SAF feedstock landscape.

Ebikade notes that global food security concerns remain a factor in how the issue is viewed internationally, even when local production systems differ.

Csonka stresses that SAF development is not tied to a single crop or region. The strategy depends on sourcing feedstocks suited to local agronomic conditions worldwide.

McCurry points to a broader awareness gap and says consumers often do not realize how much of modern agriculture already feeds energy, industrial and animal production systems rather than directly supplying food. That lack of understanding shapes reactions to new uses for agricultural materials.

SAF Creates New Questions for Seed Companies and Researchers

For the seed sector, the emergence of sustainable aviation fuel raises strategic questions.

What crop systems produce the most efficient biomass?

Which traits improve conversion outcomes?

How should residues be managed and valued?

Where will regional supply chains develop?

How will new markets affect planting decisions and breeding priorities?

The SAF market does not hinge on a single technology breakthrough. It depends on incremental gains across genetics, agronomy, logistics, processing and policy.

Opportunity and Risk Will Grow Together

Sustainable aviation fuel sits at the intersection of climate goals, energy markets and agricultural production. Its trajectory will be shaped as much by economics and supply chain realities as by technological innovation.

Aviation’s demand for lower-carbon fuels is unlikely to disappear. At the same time, cost pressures, infrastructure challenges and public perception will continue to influence adoption.

For seed companies and researchers, SAF represents both a potential market and a complex system that requires careful navigation. Feedstocks must perform agronomically, economically and industrially. Messaging must connect global sustainability goals with farm-level realities.

If sustainable aviation fuel scales, it will do so because agriculture provides reliable, scalable and economically viable inputs. And the seed industry will play a central role in determining whether that future becomes a niche pathway or a defining new market.